Early in peak tornado season, 2023 has already set records

Early in peak tornado season, 2023 has already set records

As spring takes hold across the country, traditionally the most active season for tornadoes, the year has already set records.

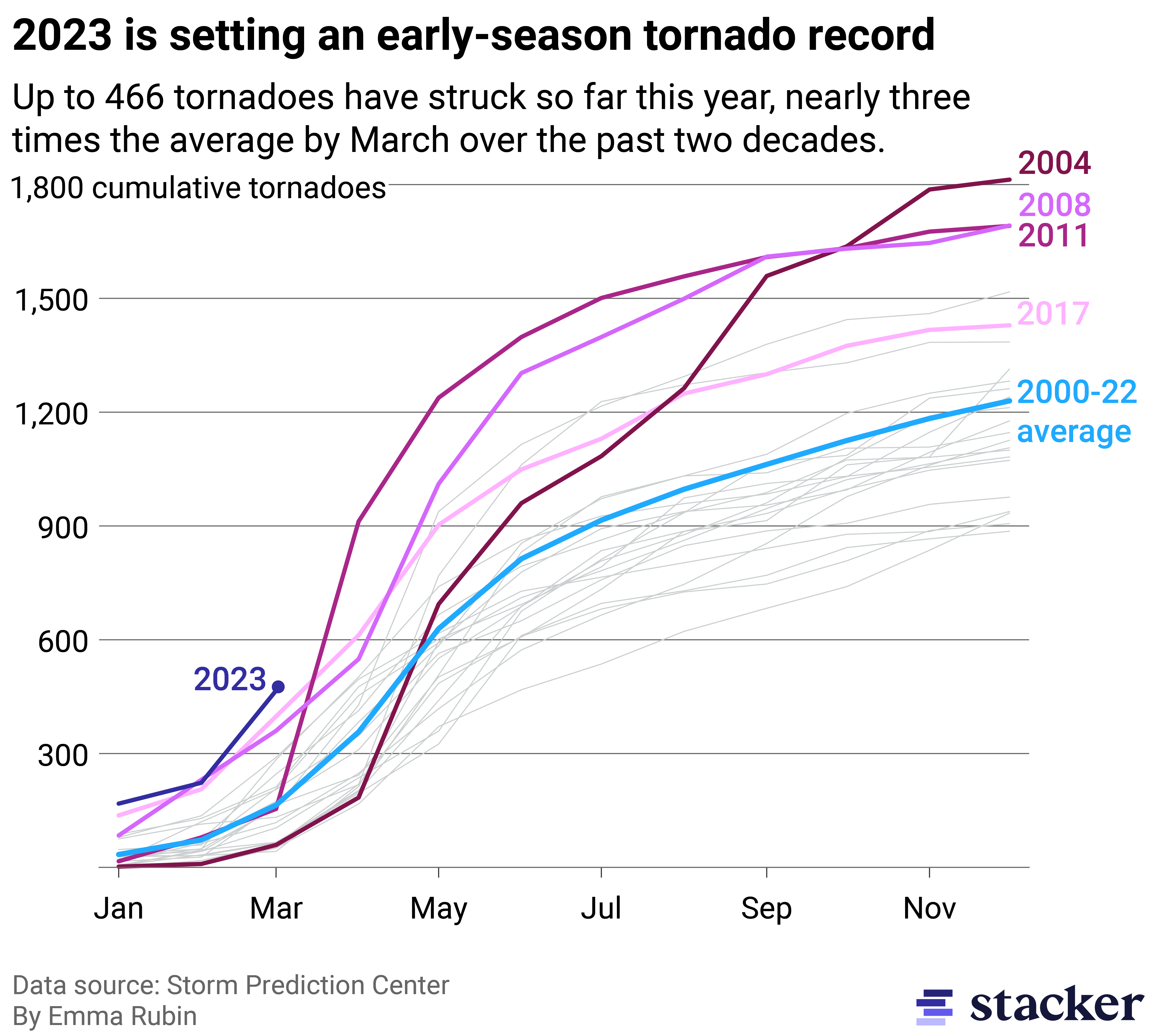

Over 400 tornadoes have touched ground in the U.S. this year, the most ever recorded in the first three months of the year and over twice as many as the average for the same time frame between 2000 and 2022.

Remarkably, nearly a quarter of 2023's tornadoes happened on a single day: March 31. Storms across the South and Midwest resulted in over 30 deaths. At present, it's the fourth-highest number of tornadoes ever recorded in a single day.

In a conversation with Stacker Senior Data Reporter Emma Rubin, NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center Warning Coordination Meteorologist Matthew Elliott pointed out that the alignment of atmospheric conditions created ideal circumstances for tornado outbreaks across a large area of the central U.S. at the end of March. "Thankfully, days like these are relatively rare, with an event of this magnitude perhaps occurring every 5-10 years," Elliott said.

What's behind the record numbers?

More frequent wind storms delivered record precipitation in the West. As these storms passed over the Rockies, they met moisture blowing upwards from the Gulf of Mexico. This front created low-pressure areas, an environment from which thunderstorms and, eventually, tornadoes can emerge.

"What's really been unique this year is that the moisture has been readily available," Elliott said.

In other years, cold fronts have pushed moisture in the air further into the Gulf of Mexico, but warmer conditions in the South kept this moisture closer to the coasts this year, spawning more thunderstorms.

What this year also has in common with other highly active tornado seasons is La Niña conditions. During La Niña, unusually cold temperatures in the Tropical Pacific push the jet stream, a strong west-to-east gust of wind further north, contributing to regional climate conditions that favor the formation of low-pressure systems in the tornado alley area.

The role of climate change

Climate change's impact on tornado frequency and severity is hard to assess in part because quality data only dates back two decades.

The NOAA Storm Prediction Center has records dating back to 1950, but it wasn't until after a National Weather Service modernization effort in the 1990s that tornado count data became more robust. Data collection today does a better job of capturing weaker tornadoes that would have been missed throughout much of the 20th century.

Even though people in tornado zones may regularly hear about watches in the news, climatologically, tornadoes are rare. Just over 1,000 happen annually—a fraction of the number of severe thunderstorms from which they emerge—limiting the sample size of tornado data further.

Record days, like March 31 this year, spike incident counts, also making it harder to parse out longer-term trends. What available data does suggest is that climate change could shift the seasonality of tornadoes. Spring is when the wind storms peak, but more cool seasonal events could happen in place of summer storms and reach further north than usual. In December 2021, two tornado outbreaks occurred unusually far north for that time of year, including several that hit Minnesota, the first December tornadoes in the state's history.

Research has also shown how Tornado Alley could shift. A study published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society found supercell thunderstorms—severe storms tornadoes can emerge from—will become more frequent with warming temperatures, moving further east from the Great Plains and into areas with higher population density.

What the rest of the season has in store

Some of the busiest tornado seasons began relatively calmly. 2011 had 154 tornadoes between January and March before ending with 1,691—one of the highest totals ever recorded—by the end of the year. Last year began with a high number of tornadoes but ended with a relatively average count.

"We can't use with any predictive power what has happened over the past few months to gauge what's going to happen over the next few months," Elliott said.

Even without long-term predictions, people who live in tornado zones should stay prepared so they are ready when watches and warnings are announced. A watch indicates favorable conditions for a tornado to form, while a warning means one has formed or is about to form. When a warning is sent out, people should follow their severe weather safety plans, finding a basement or an interior room without windows on the lowest floor.

Elliott emphasized the importance of having multiple ways to receive information during storms, including radio, in the event of lost power. Residents should also become familiar with their local warning system. Sirens, which indicate tornado or severe weather warnings, are not always available in smaller communities.