Dozens of cities are paying for gunshot detection tech they may not need

This story was produced by The Trace and reviewed and distributed by Stacker.

Dozens of cities are paying for gunshot detection tech they may not need

In June 2023, the town council in Phillipsburg, New Jersey, voted unanimously to install the gunshot detection service ShotSpotter. The town would get the system up and running in a few square miles of the city using $297,000 in federal COVID-19 relief funding, reports The Trace.

"Crime is an issue, but it's not unique to Phillipsburg," Councilmember Keith Kennedy said after the vote. "It's in every town and city around us." ShotSpotter, which alerts police to shootings through acoustic sensors positioned on lampposts and streetlights, "will be a step toward dealing with crime," he said.

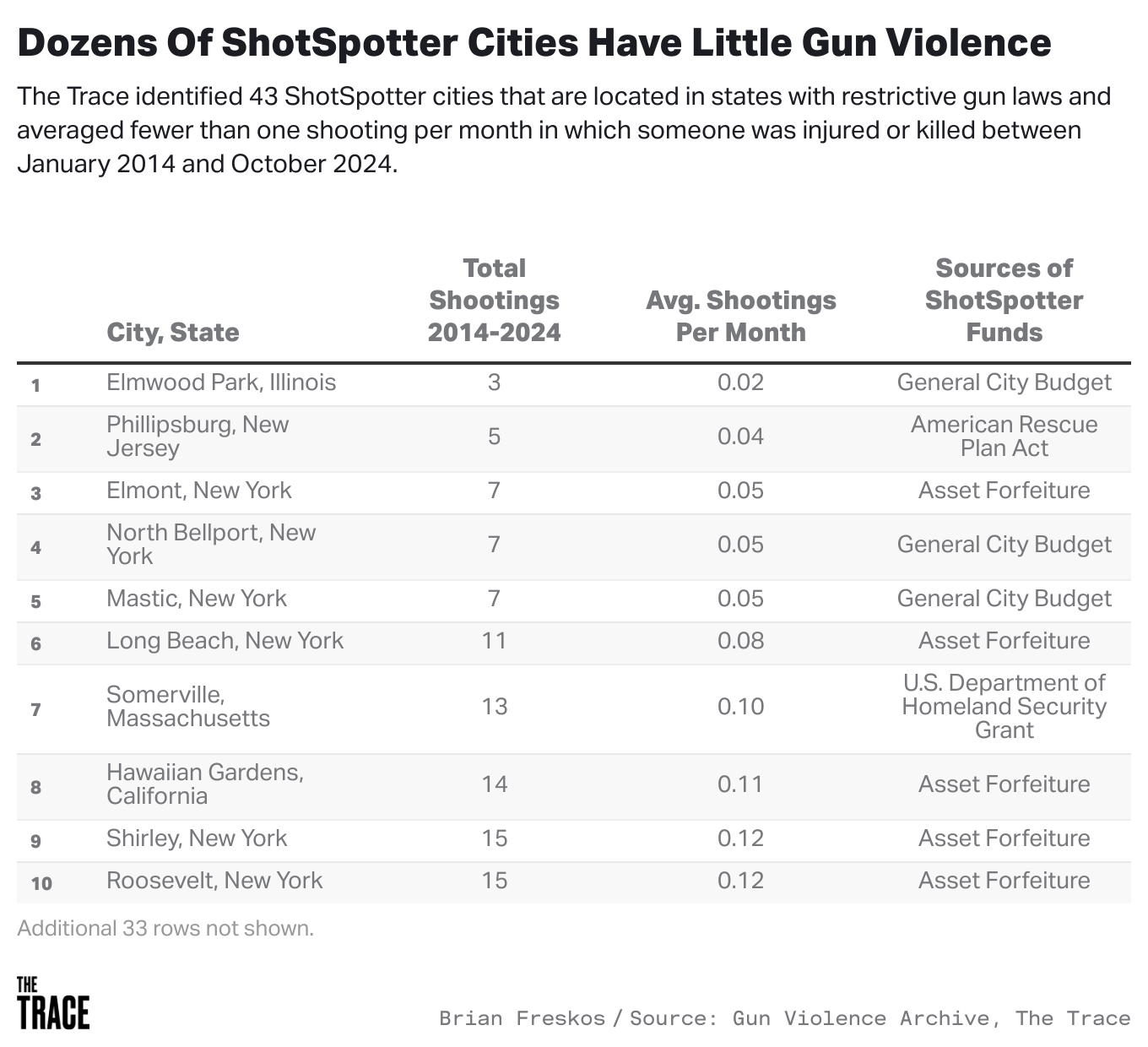

There's one thing Kennedy and other city leaders didn't mention: While gun violence may be an issue in the United States, it has rarely touched Phillipsburg. The town of 15,000 people on the Pennsylvania border has had a total of five shootings in the past decade in which someone was injured or killed, according to the Gun Violence Archive, which tracks gun violence through media and police reports. And the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that New Jersey had the second-lowest rate of gun death in the country last year.

So does Phillipsburg even need ShotSpotter?

In a new analysis by The Trace, 62 cities that have installed ShotSpotter averaged fewer than one shooting per month in which someone was injured or killed over the past 10 years, according to Gun Violence Archive data. Of those 62 cities, 43 of them—including Phillipsburg—were located in states that received an "A" grade by the gun violence prevention group Giffords for their strong gun restrictions.

For cities with scant gun violence, strong gun laws, and small budgets, critics say the money would be better spent elsewhere.

"To be perfectly frank, when I hear of some towns purchasing ShotSpotter, I'm confused," said Eric Piza, a criminology professor at Northeastern University who has published studies on the technology. "ShotSpotter is a tool to more effectively respond to gun violence. A requirement of that tool meeting its goals would be some level of a gun violence problem."

In a written response to questions, a spokesperson for SoundThinking, the company behind ShotSpotter, said the need for timely and accurate gunfire detection is critical even in low-violence cities. "Irrespective of where ShotSpotter is deployed, the technology ensures readiness, supports law enforcement in responding quickly and effectively, and reinforces public safety," the spokesperson said. "Cities that adopt ShotSpotter are addressing this challenge proactively, ensuring they have the tools to address gun violence and providing residents with peace of mind."

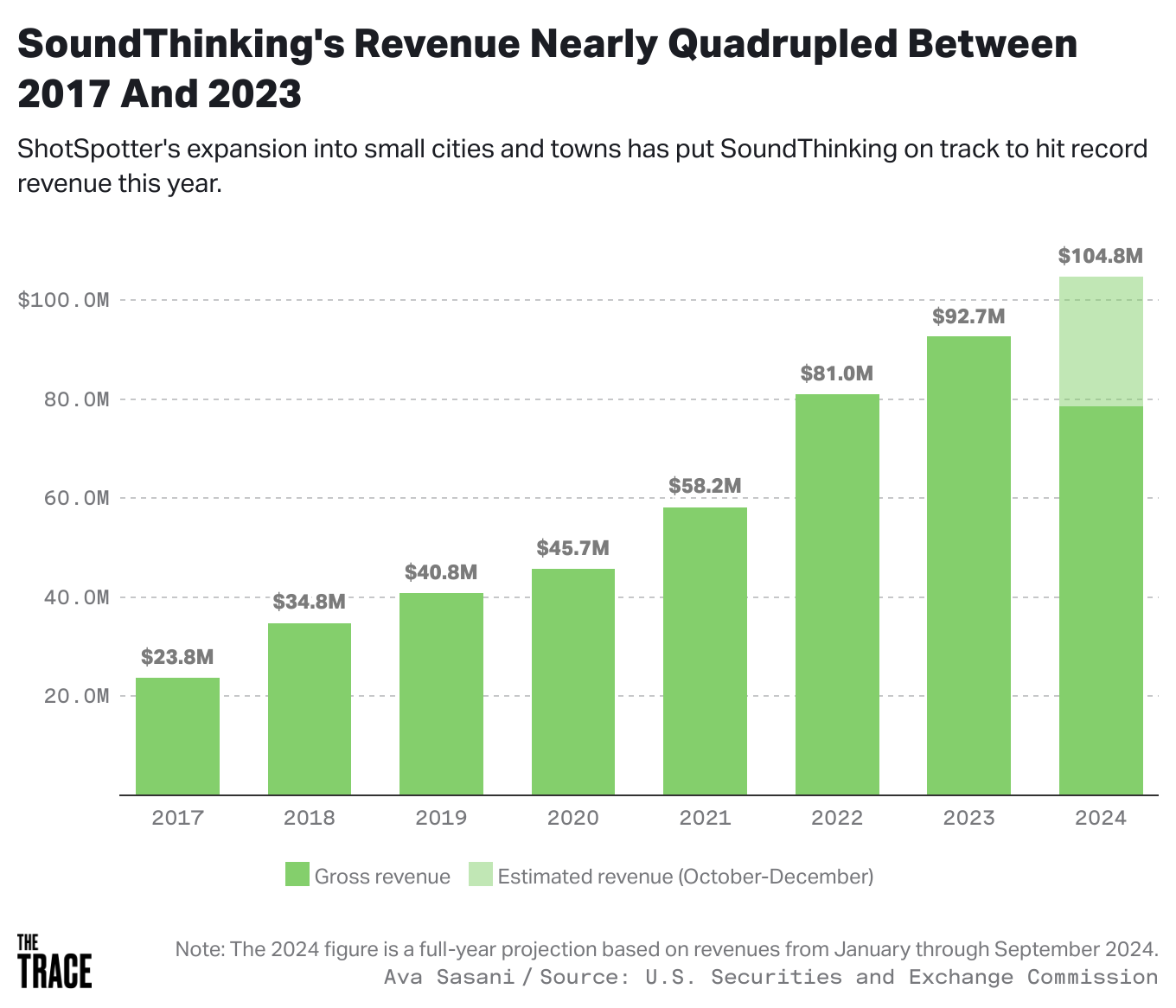

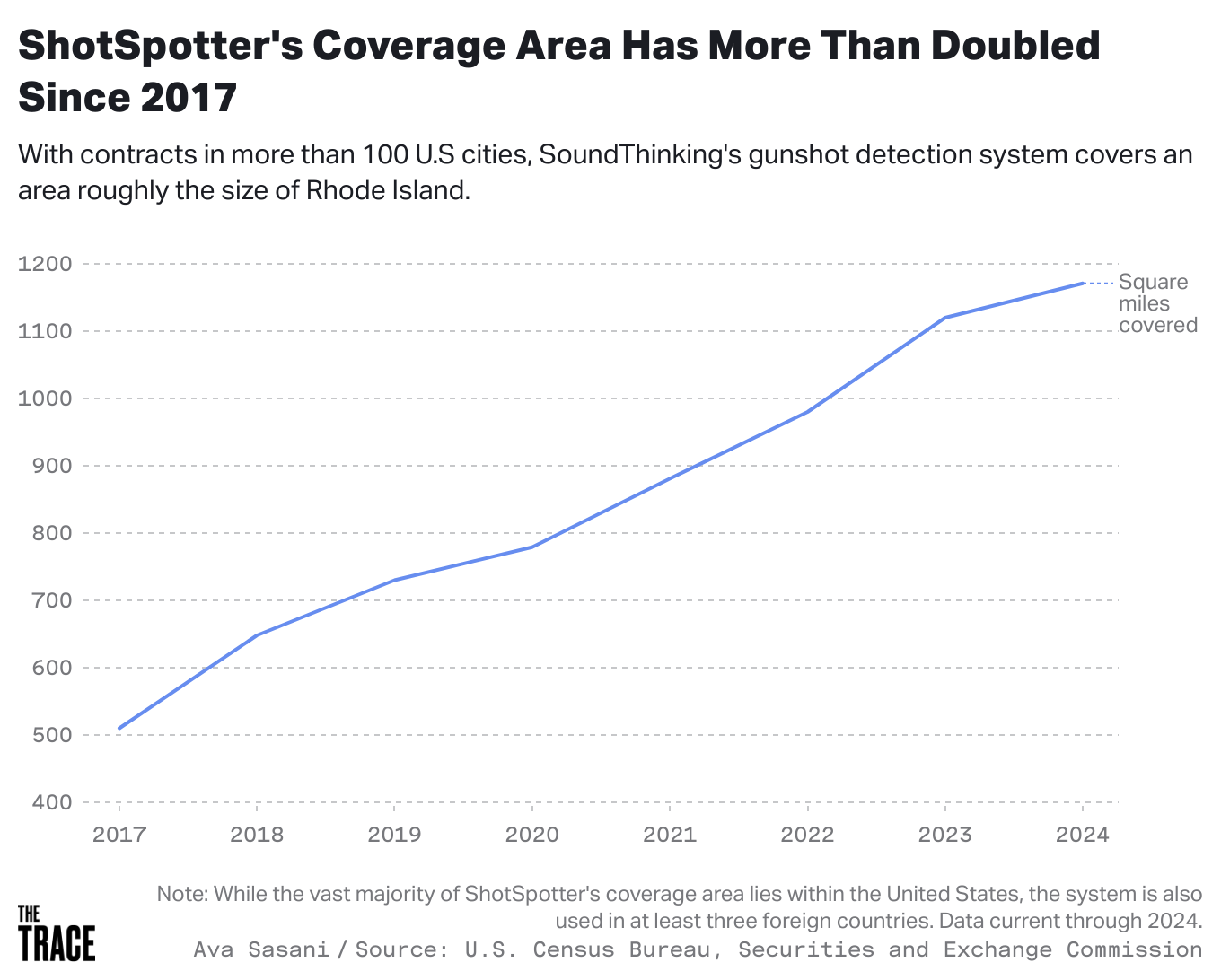

ShotSpotter is present in more than 170 cities, communities, counties, and university campuses, according to SoundThinking. Filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission indicate that the expansion into small cities and towns has caused ShotSpotter's coverage area to more than double over the past eight years. Meanwhile, SoundThinking's revenue has quadrupled from $24 million in 2017 to $93 million in 2023. The company is on track to hit record revenue this year.

ShotSpotter's Mixed Track Record

ShotSpotter, which launched in Northern California in the mid-aughts, is more closely associated with big cities like Chicago, New York, and Washington, D.C. But in recent years, those cities have faced pressure to abandon the system as researchers and community activists criticize it as an ineffective technology that doesn't prevent shootings and leads to overpolicing in Black and brown communities.

Amid the backlash, SoundThinking has pursued dozens of smaller markets—like Phillipsburg—that were more receptive to the technology. But those smaller cities are far less likely to have the volume of gun violence that justifies the need for the system, which typically costs $65,000 to $90,000 for each square mile of sensors.

David Chipman, a former federal law enforcement agent who served as ShotSpotter's senior vice president of public safety solutions from 2013 to 2016, said low-violence cities that adopt the system are just preparing themselves. "Violence might not be at your doorstep today, but we're in an interconnected country," he told The Trace. "Those cities have adopted a zero-tolerance policy for gun violence. For them, it's an early warning sign. So if you have Shotspotter and you have zero gun violence, it's because you never want to have it."

Piza, the Northeastern researcher, has found that while ShotSpotter does not improve case clearance rates or decrease crime, the technology confers other benefits, like the increased collection of ballistic evidence and more gun recoveries. A 2023 cost-benefit analysis of ShotSpotter in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, which has had the technology since 2021, found that the response time to gunshots or gunshot-like sounds flagged by ShotSpotter is "significantly quicker than those called in by residents," and police recovered guns or shell casings in more than 600 incidents, leading to more investigations.

But the largest peer-reviewed study of the technology found that it didn't significantly reduce gun deaths or increase public safety. A July audit by the New York City Comptroller found that police are sent to alerts that aren't actually shootings 87% of the time and are wasting thousands of hours responding to these false alarms. In Chicago, where the decision to not renew the city's $10 million ShotSpotter contract sparked a political power struggle between the mayor and the City Council, a recent analysis by South Side Weekly and Type Investigations found that ShotSpotter missed more than 20% of shootings and discharges in the city between January 2023 and August 2024.

The SoundThinking spokesperson said the peer-reviewed study was "flawed" because it used data from areas where ShotSpotter was not deployed. In response to New York City's audit, the company said its "alerts provide critical support and are often the only way police receive the information needed to respond quickly, render aid to victims, save lives, collect critical evidence, and take dangerous criminals off the streets."

Funding ShotSpotter

Cities fund ShotSpotter in a variety of ways: municipal and police budgets, state and federal grants, and even private donations. Of the 43 cities identified by The Trace, 30 used city budgets to pay for the technology. Of those, eight cities used the proceeds from asset forfeiture, four cities tapped their police budget, and two cities reappropriated money from the county prosecutor's office. One city—Pleasantville, New Jersey—imposed a 2.5-cent increase on the municipal tax rate to pay for ShotSpotter.

Twelve of the cities paid for ShotSpotter with federal funds. Phillipsburg and East Orange, both in New Jersey, used federal COVID-19 relief funds provided by the American Rescue Plan Act. Five cities, all in Massachusetts, used grants from the Department of Homeland Security's Urban Area Security Initiative, which is intended to help guard against acts of terrorism. Two cities used Department of Justice grants, and another two cities paid with private funding. The pharmaceutical company AbbVie, which is based in North Chicago, Illinois, subsidized that city's ShotSpotter.

The Debate Over ShotSpotter Based on Cost, Effectiveness, and Community Impact

ShotSpotter encourages cities to apply for government grants to pay for its services, and the company works with local officials to secure funding. A 2022 NBC News investigation found that ShotSpotter—which rebranded as SoundThinking the following year—"exerts influence at both ends of the federal money pipeline, lobbying Congress and federal agencies for grants and other spending programs that can be used to pay for its products, while also shepherding local police departments through the process to obtain that money."

The SoundThinking spokesperson told The Trace that the company's partnerships with cities enable them "to adopt ShotSpotter without compromising other critical budget priorities."

According to a review of city council meetings by The Trace, most of the funding resolutions and appropriations in the 43 cities passed through local governing bodies with little to no resistance from elected officials or their constituents. Opposition, when it did come, was brief.

Newburgh, New York, adopted ShotSpotter in 2016. Four years later, after a patch of pandemic-related violence, city officials wanted to renew the system for two more years. City Councilperson Omari Shakur was the lone voice of dissent.

"We're paying somebody $297,000 to listen to some shots," he said, according to the City Council's meeting minutes. "You know how many people we can hire in our community with that?"

Shakur still feels that ShotSpotter is unnecessary, and that the money would be better spent on more beat cops and anti-violence efforts. "When officers are patrolling on the ground, you talk to people, and now you know more likely what happens on the street," Shakur told The Trace. "And if something does happen, you'll find out quicker, because you have a relationship." That plays out at the community level as well. "Most of the time before ShotSpotter goes off, I'm already calling police, because I got the phone call" from someone in the neighborhood, he said.

ShotSpotter seems especially wasteful in the summer when people set off firecrackers, Shakur said. "Now you're sending patrols out when they could be somewhere preventing something." ShotSpotter "is a tool," he said, "but it doesn't prevent anything."

Shakur's concerns highlight a gap in the ShotSpotter system: It's only effective at preventing gun violence if police take every alert seriously—if they do more than "listen to some shots." Chipman, the former ShotSpotter executive, said one problem with ShotSpotter's rollout on a city-by-city basis—as opposed to, say, audio surveillance that blankets the country like a mobile network—is that most police officers will investigate a ShotSpotter alert only if someone is shot. If police don't go to the scene, they fail to collect evidence that could help solve subsequent shootings.

Police officials say many people who hear gunshots in neighborhoods plagued by violence are reluctant to call 911 for fear of retaliation, so audio gunshot detection is a more reliable way of reporting shootings.

"I think cops, like most people, do what they can get away with doing," Chipman said. "It's only very elite, committed law enforcement who are treating every alert to gun violence like it could be a homicide. If everything looks quiet, are you going to get out of your car and open a case if there's shell casings on the ground? It doesn't happen."

Is It Worth It?

Some cities identified by The Trace may not have a gun violence problem within their own borders, but are near ones that do. One of those is Elmwood Park, Illinois, on Chicago's northwestern edge. Elmwood Park had just three shootings in the past decade, according to Gun Violence Archive. But the city signed a three-year contract in May for sensors covering two square miles, at a total cost of $243,300, paid for with asset forfeiture funds.

Village President Angelo Saviano admitted to a local news station that the town doesn't see a lot of shootings, but Chicago's ShotSpotter sensors would pick up shootings on the town's perimeter. After Chicago shut its sensors off, Elmwood Park wanted sensors of its own. ShotSpotter passed the board of trustees unanimously. "Maybe the technology isn't perfect," Saviano told a radio station in February. "But it's something that we feel is necessary for us to have."

ShotSpotter may offer even less bang for the buck when considering that it doesn't capture every shooting. The company says it "will detect and accurately locate, within 25 meters of the actual gunshot location, 90% of the unsuppressed, outdoor gunshots fired inside the contracted coverage area using standard, commercially available rounds greater than .25 caliber." That excludes most shootings that happen indoors, involve .22-caliber bullets, or a gun with a silencer attached.

The High Costs and Controversies of ShotSpotter in Low-Crime Communities

Officials in cities with low gun violence who want to adopt ShotSpotter must convince the public it's necessary without making the community seem unsafe. It's a delicate dance. Last year, when the police commissioner in Suffolk County, New York, lauded the return of ShotSpotter after a failed pilot several years earlier, he admitted that the county "is considered one of the safest communities in the country." Nevertheless, lawmakers dissolved a county campaign finance board to pay for the technology.

"Deploying ShotSpotter is not an indication of danger, just like seatbelts in a car do not indicate the car is unsafe," the SoundThinking spokesperson said.

Because of the high cost of ShotSpotter, cities can't afford to cover every block, so officials narrow down the most violent areas, usually just two or three square miles, and place sensors there. That focus on the most disproportionately affected neighborhoods is viewed as pragmatic by law enforcement and city officials, but critics say it's a recipe for overpolicing.

In 2022, the MacArthur Justice Center filed a class action lawsuit against Chicago alleging that police disproportionately used physical force against Black and Latino men during ShotSpotter calls. "Every one of these deployments creates a dangerous, high-intensity situation where police are primed by ShotSpotter to expect to find a person who is armed and has just fired a weapon," the center alleged in a court brief. "Residents who happen to be in the vicinity of a false alert will be regarded as presumptive threats, likely to be targeted by police for investigatory stops, foot pursuits, or worse."

The center cited the case of Michael Williams, who spent a year in jail on a murder charge based on a misinterpreted ShotSpotter alert.

Issues surrounding ShotSpotter have attracted the attention of Congressional lawmakers, who are concerned that the disproportionate focus on certain populations is a violation of the federal Civil Rights Act. In May, a group of Senate and House Democrats called on the Department of Homeland Security's Office of Inspector General to investigate the use of federal grants on a technology they say contributes to the "unjustified surveillance and over-policing of Black, Brown, and Latino communities."

One of those lawmakers, Oregon Senator Ron Wyden, said in a statement that the technology is not an effective way to make communities safer or to catch criminals. "I have a lot of concerns about how it biases policing in ways that hurt low-income and minority communities in particular." He added there's a possibility for the company "to use its relationship with local law enforcement to balloon their spending on technology with add-ons, at the expense of investments in things that actually keep communities safe."

SoundThinking said demographics are not considered when deploying ShotSpotter. "ShotSpotter deployments are determined by each jurisdiction, based on objective historical crime data, with occasional requests from elected officials who want the technology deployed within the communities they represent to enhance public safety," the company's spokesperson said. "All residents who live in communities experiencing persistent gunfire deserve a rapid police response, regardless of race or ethnicity. ShotSpotter provides this."

However, even when the technology is free, there can be other costs. Somerville, Massachusetts, is one of several small cities that get ShotSpotter free because it's part of the Metro-Boston Homeland Security Region and receives the Department of Homeland Security's Urban Area Security Initiative grant. Even though ShotSpotter is not costing Somerville a dime, Councilor Willie Burnley Jr. has spent the past year trying to persuade city officials to scuttle it.

"We've seen reports from our own police that tell us that ShotSpotter is ineffective, that it sends them to the wrong place," Burnley told The Trace. False alerts are "incredibly dangerous for the public," he said. "Police arrive on the scene expecting someone who has a gun."

"One of the arguments I hear from colleagues who are in support of ShotSpotter is that it's basically a free tool that we get, and if it helps one person, then that's good enough," Burnley, Jr. said. "But what if it hurts one person?"

According to Burnley, most of Somerville's ShotSpotter sensors are placed in communities of color, a disparity that bothers him. "Just because ShotSpotter is free does not mean that we should place microphones all across our community, particularly in communities of color, to surveil people," he said. It's especially unnecessary in a place like Somerville, which is 4.3 square miles and everyone knows everyone. "We talk to our neighbors here," he said.

For many small towns, federal funding may be too tempting to pass up. But "that grant money does not have to go towards technology," said Piza, the criminologist from Northeastern. "Doing things like hiring more police officers to conduct community policing and strategies like problem-oriented policing frankly have much better track records for preventing crime than technological solutions do."

Trace editing fellow Agya K. Aning assigned, edited, and contributed research to this story. Reporter Chip Brownlee contributed data analysis.