First-generation students feel the impacts after the Supreme Court strikes Biden's loan forgiveness plans

This story originally appeared on Best Universities and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

First-generation students feel the impacts after the Supreme Court strikes Biden's loan forgiveness plans

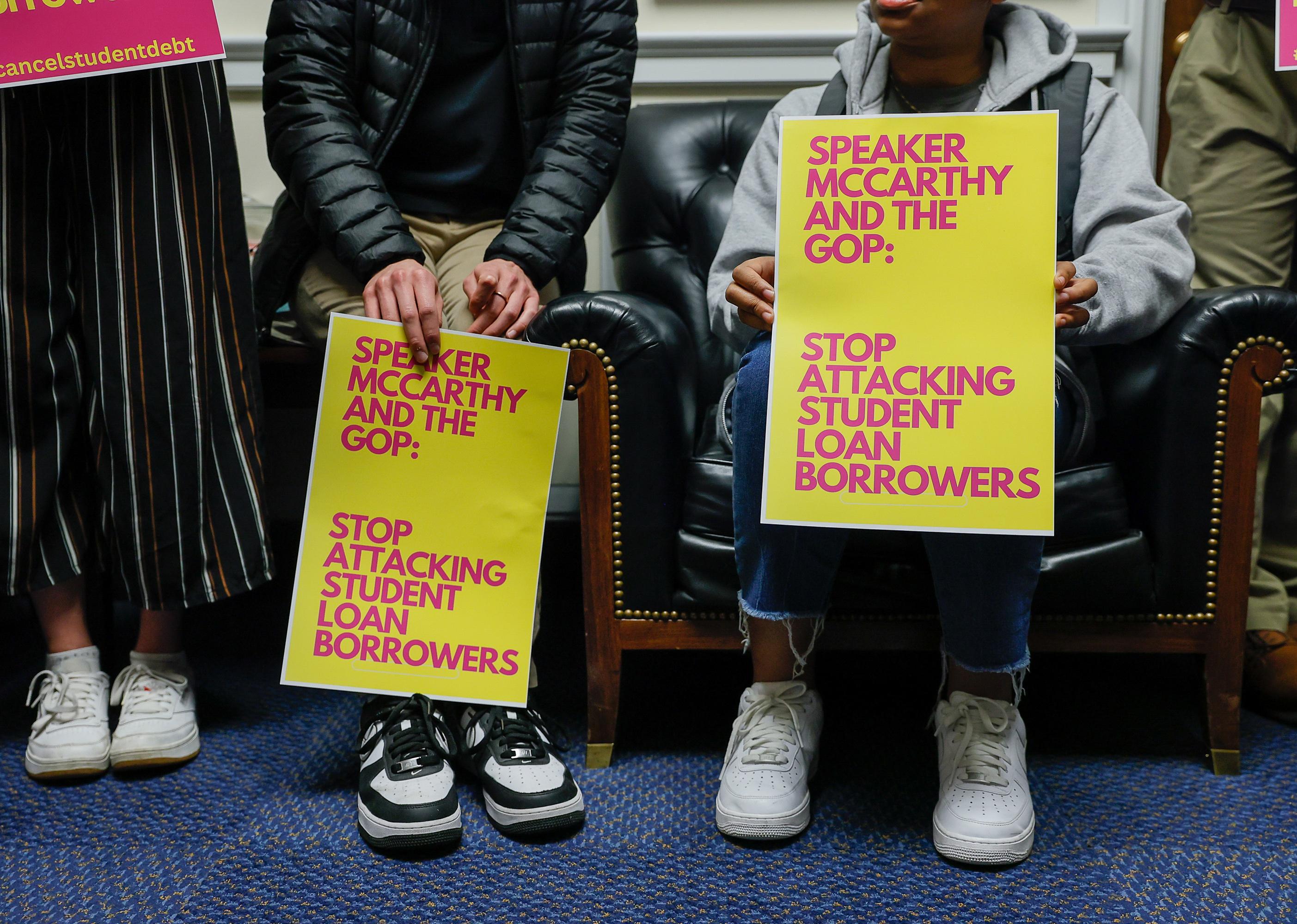

More than 43 million Americans had to rethink their financial plans for the future when, on June 30, 2023, the Supreme Court struck down the Biden administration's proposed plan to cancel up to $400 billion in student debt.

President Lyndon B. Johnson expanded access to higher education when he authorized the Higher Education Act of 1965, which made student loans available to anyone. However, the involvement of private investors in later years reshaped the landscape of the student loan industry.

As of June 2023, Americans shoulder more than $1.76 trillion of combined private and federal student debt. About 93% of this debt is federal. In pursuing a bachelor's degree, the average public university student amasses $25,969 in debt.

College tuition costs have increased drastically in the past 20 years, outpacing the average increase in median household wages. A U.S. News report tracked the change in tuition and fees at 440 prominent national universities from 2003 to 2023. At private universities, tuition and fees increased by 134%, while the out-of-state cost for public universities jumped by 141%. In-state prices for public universities rose by 175%.

The sticker price for college has gone up, but many note that adults with at least a bachelor's degree have better lifetime earnings than those without one. Still, the extent to which a four-year degree can boost a person's economic status also depends on many factors, including whether the student is a first-generation college graduate.

Best Universities examined what the end of Biden's loan forgiveness program means for first-generation students and graduates, referencing research and data from the Federal Reserve and the National Center for Education Statistics.

First-generation college students are more likely to take out loans to complete their education. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 74% of first-generation college students use loans to earn their degrees compared to 65% of non-first-generation students.

In general, first-generation college seniors borrowed more and at a greater frequency than those with college-educated parents. The first-generation students in the class of 2016 who borrowed to fund their education took out an average of $30,700 in loans—while their classmates who were not first-generation students averaged $28,700 in loans.

First-generation students also typically borrow more in total loan amount and at a higher frequency than their peers in their first year, according to the NCES. Loans with higher interest rates carry a greater risk of default—and data from the Federal Reserve shows that first-generation students have a harder time making loan payments.

In 2021, about 15% of first-generation students were behind on loan payments, which is about twice the rate as those who reported having at least one parent who completed a bachelor's degree. According to the Institute for College Access and Success, as of October 2018, about 23% of first-generation students had defaulted on their student loans within 12 years, compared to 14% of those with college-educated parents.

The consequences of defaulting on federal student loans can be very costly. In general, after 270 days of nonpayment, borrowers may face ineligibility for payment plans and further aid; reports to credit bureaus, which affects their ability to get other loans; and even wage garnishment. When a student's loan debt exceeds their ability to repay, deferment or forbearance can help temporarily.

College graduates who have college-educated parents also have higher incomes on average than first-generation college graduates according to the Pew Research Center, even when controlling for other variables including race, sex and year graduated. First-generation graduates who are men earn approximately 11% less per year, while first-generation graduates who are women earn approximately 9% less per year, according to the federal Baccalaureate and Beyond Longitudinal Study.

However, first-generation college graduates enjoy higher incomes, long-term economic outcomes, and social mobility than those without higher education, according to a report by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Many programs exist to equalize educational attainment in spite of the increasing costs. Some teachers, public service workers, government employees, nonprofit workers, and medical professionals may qualify for federal student loan forgiveness. Additionally, various career, military, and volunteer programs qualify borrowers for relief.

Story editing by Jeff Inglis. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.