From added sugar to sodium, here's how US dietary recommendations have changed over the last 50 years

This story originally appeared on Northwell Health and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

From added sugar to sodium, here's how US dietary recommendations have changed over the last 50 years

More than 30 million school-aged children's menus will change in fall 2025 to reflect the latest dietary guidelines recommended by the U.S. government. Their new fare will limit added sugars in cereals and yogurts—increasingly over time—and reduce sodium in school breakfasts by 10% and lunches by 15% starting July 1, 2027.

"Like teachers, classrooms, books, and computers, nutritious school meals are an essential part of the school environment, and when we raise the bar for school meals, it empowers our kids to achieve greater success inside and outside of the classroom," Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack said in a statement announcing the change.

The government didn't make these changes willy-nilly. The Department of Agriculture's latest bid to make school lunches healthier was shaped by the ever-evolving Dietary Guidelines for Americans, a document published every five years by the departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services after careful consideration by the nongovernmental advisory panel. These influence the diets of 1 in 4 Americans who eat from the menus in schools, prisons, military bases, and other federal food programs. The two agencies have collaborated on guidelines since 1980. The next update is due in 2025.

Before these guidelines evolve yet again, Northwell Health partnered with Stacker to see how U.S. dietary guidelines have changed—and if they've stood the test of time—using historical documents, academic research, and news articles.

Nutritional nudges encourage more evidence and less fad diets

The guidelines were established for good reason: A cacophony of conversation around fad diets and what's healthy left Americans confused about what information to believe when they're in the grocery aisle.

Long before the public was captivated by social media influencers offering tips and advice on nutrition and savvy marketing campaigns by food manufacturers themselves—nutritional campaigns like the food wheel of the '80s and the food guide pyramid of the '90s helped ordinary people perceive the healthiness of food.

Over time, the guidelines have become stricter and more detailed, while its authors try to make them more accessible for the average person. They no longer recommend specific nutrients but rather try to take a holistic view of the food and beverages, knowing people often consume the same ones again and again over many meals.

Despite shifting approaches over the decades, what's stayed the same is the constant debate and varying opinions among experts. Though guidelines have been available for decades, Americans' diets still don't get a passing grade. "It's pretty self evident that the guidelines have done nothing to prevent our country's epidemics of obesity and diabetes," Nina Teicholz, executive director of the Nutrition Coalition, told The New York Times.

1980: Avoid sugar and high-fat foods

The early days of the guidelines left much up for interpretation: "Avoid too much sugar…Avoid too much fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol," without giving Americans a yardstick of how much "too much" was. The 1980 guidelines say the health hazard inherent in excessively eating sugar is tooth decay, and disputes it causes diabetes, heart attacks, or blood vessel diseases.

While a diet with excess sugar doesn't directly cause these conditions, we now know it increases the risk of obesity, according to a review of scientific literature focused on Americans published in a 2019 issue of the Polish Journal of Food and Nutrition Sciences. Research published in BMC Medicine in 2023 found that more sugar also led to higher incidents of cardiovascular disease and stroke, while an umbrella review of meta-analyses published in 2023 in the British Medical Journal reported it could increase the risk of Type 2 diabetes and some cancers.

In 2020, the guidance limits added sugars and saturated fats to a maximum of 10% of one's daily calorie intake starting at age 2—a change carried over from the 1990 edition.

1985: Eat foods high in starch and fiber

In 1985, Americans were encouraged to maintain a "desirable weight" rather than the "ideal" one promoted in 1980. Foods high in starch, like bread, dry beans, peas, and potatoes, were highlighted over sugars as being healthy sources of nutrients. It also promoted consuming carbs for those looking to lose weight because it had about half the calories of fats.

Starchy foods can contribute to weight loss and better health, but we now know not all are created equal. A 2024 study in Nature Metabolism noted that naturally occurring "resistant starch," which the body can't convert to energy and thus passes through and out of the digestive system, is proven to improve the body's sensitivity to insulin and curb weight. It can be found in foods like oats, whole grains, and legumes.

1990: Balance food intake with physical activity

The 1990 nutrition guidelines were the first to directly address weight by sharing the latest research on the impacts of where body fat is stored and its links to health risks while also addressing excessive thinness.

Balancing food intake with physical activity became more apparent with the passing of the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act in 1990, implemented in 1994. It required nearly all packaged and processed foods to show their ingredients and how their portions make up someone's daily calories. This helped Americans navigate which nutrients were and weren't found in their foods.

1995: Follow the food pyramid

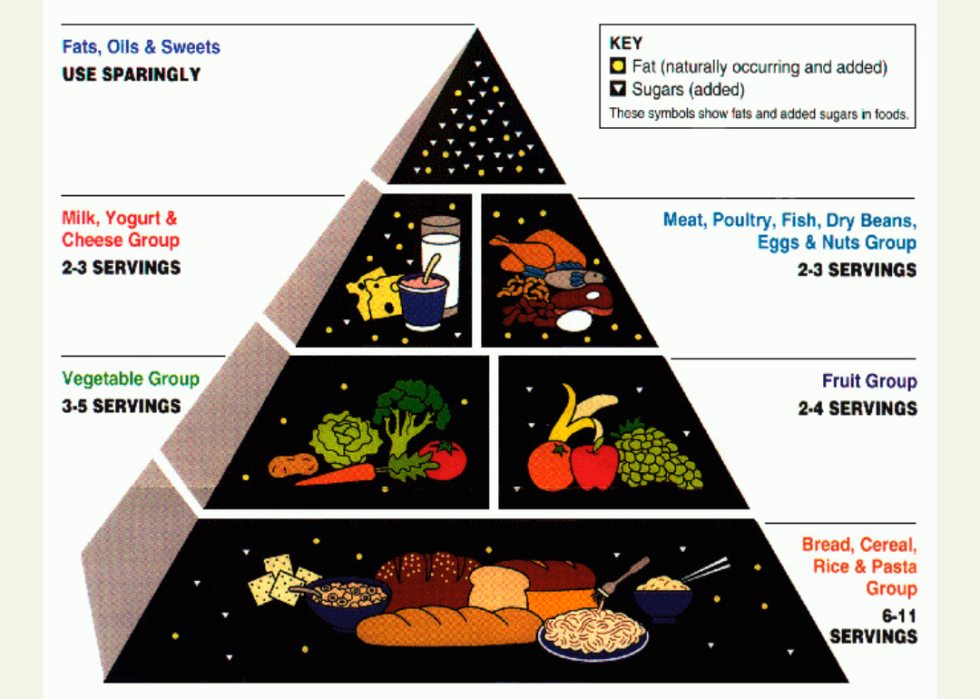

In the era of waif models appearing on TV, the nutrition guidelines focused more on recommending food items instead of particular nutrients. They became more precise with the introduction of the food guide pyramid graphic. Five food groups comprise the pyramid and make up a daily healthy diet, with grains as the foundation. The guidelines suggested 6 to 11 servings a day, followed by other food groups in lesser portions: vegetables (3 to 5 servings), fruits (2 to 4 servings), dairy (2 to 3 servings), meat and beans (2 to 3 servings).

The pyramid became widely known, but based on today's nutritional science, promoting high-carbohydrate servings and offering low-level guidance on which types of meat, dairy, and fats to choose made the popular food pyramid somewhat of a passing phenomenon.

These evolutions in eating recommendations still did little to clarify what is healthy. In a 1996 survey by the major contributor to the nutrition guidelines, the USDA, over 40% of meal planners and planners strongly agreed that "there are so many different recommendations about healthy ways to eat, it's hard to know what to believe."

2000: Eat whole grains

Once again, the 2000 dietary guidelines shifted Americans' perceptions of food. The biggest portion of the food pyramid now came with the new recommendation to especially eat "whole" grains" rather than "refined grains." Whole grains like brown rice, whole oats, bulgur, and pearl barley provide more fiber and nutrients than nonwhole grains. Eating whole grains is also a strategy to feel fuller with lower calories, according to the guidelines.

The 2020 recommendations highlighted the benefits of whole-grain foods, which have been shown to improve overall health and affect obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. This research is encapsulated in a 2022 quantitative analysis of writings on whole grains published in the Foods journal.

2005: Eat 2,000 calories a day

Finally, in 2005, Americans were given an average caloric yardstick of 2,000 daily calories consumed to help make healthier choices and simplify understanding nutrition labels. The guideline's footnotes note that the 2,000-calorie food guide is only appropriate for sedentary males 51-70 years old and sedentary females aged 19-30 years old. The guide also tailored offers for people by gender, age, and activity level.

The nuanced language and approach in 2005's guidelines reflected the advisory committee's more formal, systematic approach, which catered to policymakers, health care professionals, and nutritionists rather than the general public.

Though they thought that by appealing to nutrition professionals, their message would trickle down to the public, there were still gaps in communication. The 2,000-calorie guideline has been criticized for being a one-size-fits-all solution that could actually lead to weight gain.

2010: Limit trans fats

In 2010, a year after a new classification system was proposed to categorize foods by how much they have been processed, the guidelines recommended keeping trans fatty acids (which are formed during food processing) as low as possible to decrease the risk of chronic disease. These guidelines went to lengths to describe the various types of fats, including trans fats that are usually solid at room temperature.

Trans fats are still considered to be the worst type of fat, increasing the risk of heart disease by increasing "bad" cholesterol. The World Health Organization has called for a global, total ban on industrially produced trans fats by 2025, noting that the substance is responsible for premature deaths of up to 500,000 people due to coronary disease.

2015: Consider a Mediterranean diet

In 2015, the guidance prompted Americans to consider eating like a person in a Mediterranean country. This edition moved away from a focus on individual food groups and nutrients and instead shifted the emphasis on eating patterns or the combination of foods consumers typically eat. In addition to the U.S.-style pattern based on the USDA food patterns presented in the 2010 edition, the agencies added two other examples: the Mediterranean-style diet and vegetarian versions, which are meant to give Americans examples of healthy eating styles based on personal and cultural preferences.

The Mediterranean diet includes more fruits and seafood and less dairy than the average U.S. diet. It's still considered to be a healthy diet with its links to reducing heart disease and cancer, according to a study in the Mayo Clinic Proceedings published in 2023 and an examination of "Blue Zones"—parts of the world where people live longer and healthier lives—published in a 2024 issue of the Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders - Drug Targets journal.

2020: Try the MyPlate Plan

The introduction of the MyPlate Plan in 2020 aimed to help Americans identify foods that fit their lifestyles and life stages while being high in nutrients and weeding out those with tokenistic amounts of nutrition.

The guidelines recommend limiting or avoiding added sugars, saturated fats, and sodium. Aside from the recommendations for what to exclude, most of the guidance hones in on what to add to diets. It also acknowledges that dietary patterns should shift with age and budget.

The latest guidelines in 2020—a year the world was in the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic—did not come without controversy, however. Critics raised concerns about the fact that more than half of panel members had ties to the food industry. Others noted that questions about red meat and salt consumption were omitted. There were also no planned discussions of sustainability due to complaints from the livestock industry.

Despite these issues, health professionals continue to advocate for simpler maxims—ones that people could actually remember and put into practice. New York University nutrition expert Marion Nestle, who served on the 1995 advisory panel, told The New York Times, "In my view, the advice is the same: Eat your vegetables, don't gain too much weight, and avoid junk foods with a lot of salt, sugar, and saturated fat."

Story editing by Carren Jao. Additional research by Elena Cox. Additional editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.