The troubling link between rising rents and lower life spans: Where are renters most at risk?

This story originally appeared on Foothold Technology and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

The troubling link between rising rents and lower life spans: Where are renters most at risk?

A notice about increasing rent from a landlord has always come with a degree of heartburn. Now, researchers suggest it's linked to a higher likelihood of early death.

Foothold Technology analyzed a recent study by Princeton's Eviction Lab and data from the National Low Income Housing Coalition and the Bureau of Labor Statistics to illustrate the public health impact of limited affordable housing in the U.S. Researchers from the Eviction Lab traced the economic decision-making of people surveyed by the Census from 2000 to 2019, and matched it to death records, amounts of income spent on rent, as well as 38 million eviction filings from 2000 to 2016.

The 2024 study in the journal Social Science & Medicine found that the greater the percentage of income someone spends on housing, the higher their chances of dying. Researchers found that every 10 percentage point increase spent on rent drove a person's risk of dying higher by 8%. They also found that the threat of a potential eviction via a notice from a landlord, even if the tenant was never removed, was associated with a 19% increase in risk of death. Actually being evicted was found to be associated with a 40% increase.

Recent economic trends further suggest that the risk of death associated with rental housing instability could be affecting more and more Americans.

The post-pandemic economy saw the cost of rent rise at nearly five times the rate it had in the years leading up to the arrival of COVID-19 in 2020. Annual change in rents asked by landlords peaked at 15% in early 2022, according to Harvard University's Joint Center for Housing Studies.

Around the same time, the number of people paying a third or more of their income on housing hit an all-time high of 22.4 million households, marking the worst period of affordability ever for renters. Higher rents place a burden on low-income households, forcing them to shift their spending habits in order to keep a roof over their heads.

Researchers at the Eviction Lab found that low-income households that spent 30 to 50% of their income on rent spent about half as much on health care and one-fifth as much on food compared to households that spent less than 30% of their income on housing.

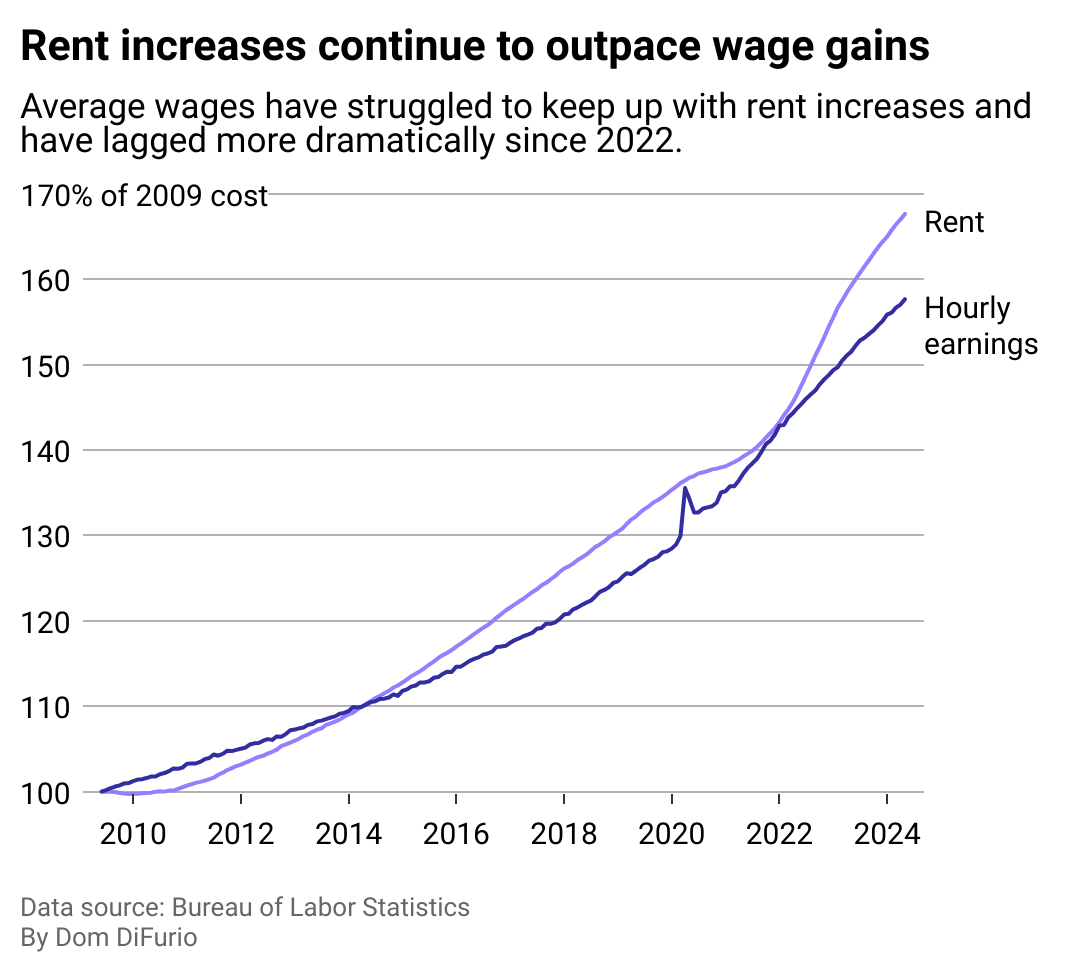

What's more, the shortage of housing exacerbated by the housing market crash in 2008 has been pushing rents up much faster than wages have grown over the past decade, leaving little room for the lowest earners to keep up.

Low-income households can't keep up

For the majority of the years since the end of the housing market bubble burst, which gave way to the Great Recession, rental costs have grown faster than wages. The growth in average hourly earnings paints a limited picture, however. Not every worker in the U.S. economy experiences wage gains the same way, and it's the lowest earners that are struggling most to keep a roof over their families' heads. Today, the U.S. is short 7.3 million rental homes for people who earn wages at or below the federal poverty level or below 30% of the area median income if that is greater, according to data from the NLIHC.

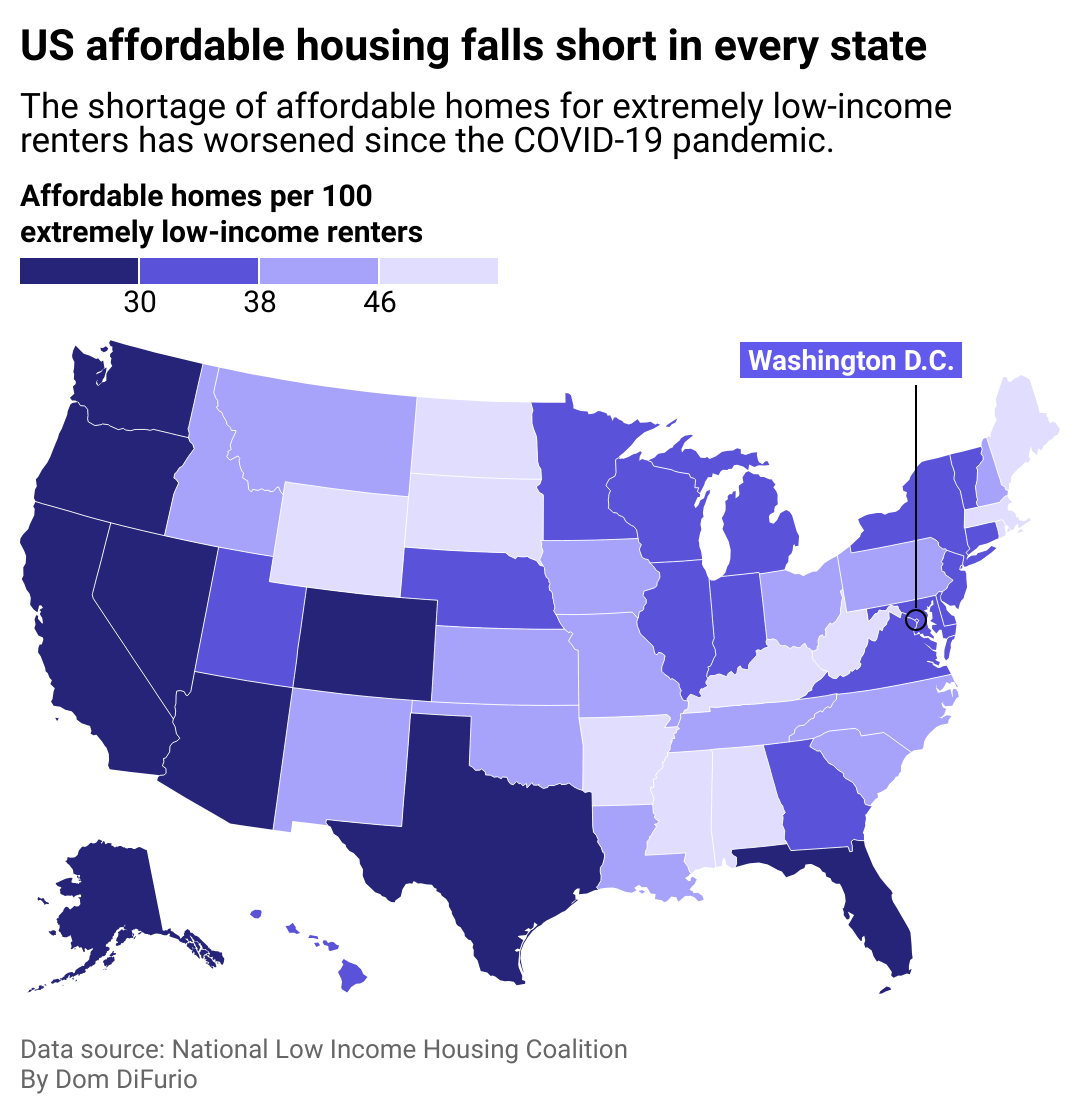

Harvard's Joint Center for Housing Studies has tracked a decline in affordable housing units available to renters over the past three decades, between 1990 and 2017. It's a problem that's only worsened since the aughts—the period studied by Princeton researchers linking higher rent costs and evictions to premature deaths. The national shortage grew by 7%, or 500,000 more rental homes, from 2019 to 2022, according to the NLIHC.

In which states are renters most at risk as the affordable housing crisis worsens?

On average, there are 34 affordable rental units for every 100 extremely low-income renters today, but availability varies greatly among states. Some of the most populous states in the country—including Nevada, Arizona, California, Florida, and Texas—are currently suffering from the largest shortages of affordable housing for renters at the lowest income levels.

The households in need of this type of housing are disproportionately Black, Latino, and Indigenous and those affected by the shortage are mostly senior citizens, people with disabilities, or a part of the workforce, according to the NLIHC. A considerable portion of working people disadvantaged by the shortage work 40 or more hours a week.

Some of those same states with expansive shortages are also seeing renters displaced by rising evictions—an issue typically discussed economically, but which the Eviction Lab's study with the Census underscores is also a growing public health crisis.

In Texas, which has one of the greatest shortages in the nation, eviction filing rates are ballooning beyond pre-pandemic levels this year. That same trend is also playing out in California, reversing a decades-long trend in which eviction filings had been falling since the Great Recession.

In Nevada, where the shortage of affordable homes is the most severe in the nation, some experts point to the affordability crisis stemming from the Golden State next door, suggesting that priced-out Californians are scooping up homes in the neighboring state.

Wages aside, housing developers tend to cite zoning problems, high labor and materials costs, and public pushback from homeowners and those who don't want to live near affordable housing as major barriers to building more. In Arizona, a coalition of local governments in the most populous county is trying to combat the negative perceptions of Americans who need affordable housing with a new initiative called Home Is Where It All Starts.

Meanwhile, President Joe Biden has identified housing as a key issue and aims to lower housing costs through various means, including mortgage relief credits to first-time homebuyers, tax credits to build or preserve millions of additional owner-occupied homes over the next decade, and rental assistance and vouchers for more than 100,000 extra households.

The rental assistance might actually save lives, according to Princeton researchers, though it would require the cooperation of Congress. According to the Eviction Lab, while rising rents and even the threat of evictions negatively impact public health, the inverse is also true: Seeing one's share of income toward rent drop over time promotes longer, healthier lives.

Story editing by Carren Jao. Additional editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.