When will the nursing shortage end?

The impact of the nursing shortage has received considerable coverage nationwide. Nurses across the country have gone on strike to protest high staff-to-patient ratios resulting from the nursing shortages.

According to estimates by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the nursing shortage has not yet reached its peak, but the agency has projected when the national shortage may end. NurseJournal looked into these projections and what closing the workforce gap will mean for nurses.

Future Look: How Long Could the Nursing Shortage Last?

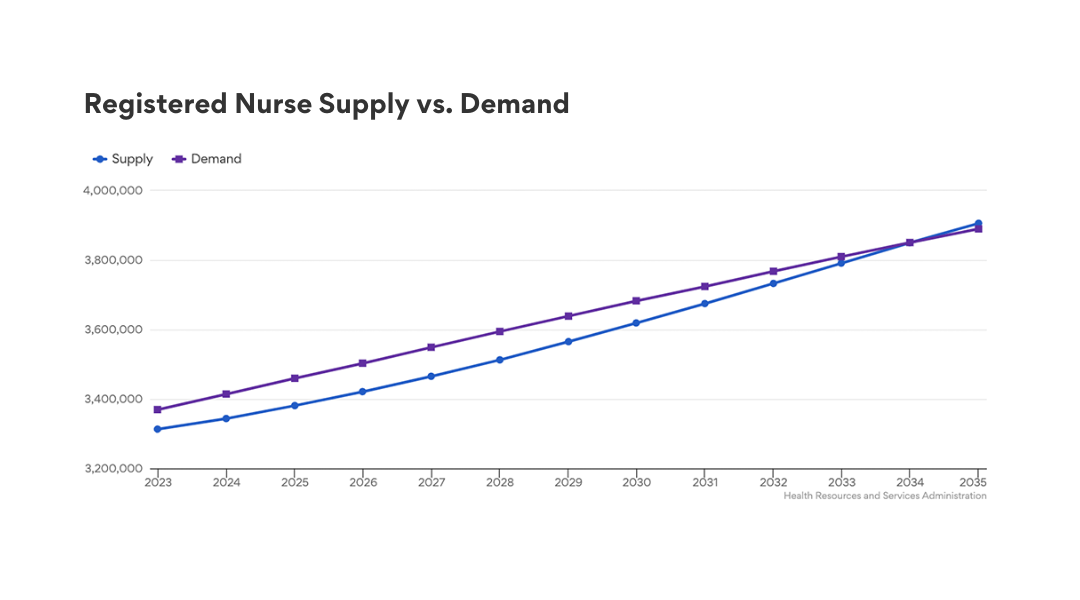

HRSA projections estimate that the shortage of full-time registered nurses (RNs) is projected to peak in 2027 and continue until 2035 — the first year where the supply of RNs is estimated to meet the national demand. As of 2023, the supply of registered nurses in the U.S. is 3,313,320 while the total demand is 3,369,610, equal to a 98% adequacy rate.

While these projections suggest that the nursing shortage could end on a national scale by 2035, regional estimates show that nursing shortages may last significantly longer in certain states.

The Health Workforce Simulation Model (HWSM) sought to assess the adequacy of the nation's workforce supply to meet the current and expected future demand. The simulation model assumes many historical patterns that impact attrition and graduation would remain the same during the forecasted period. Since the HWSM uses data from 2020, the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the profession won't be fully estimated until data is gathered and used in the model.

However, historical data does not account for the growing number of Baby Boomers reaching retirement age, which typically is associated with an increase in chronic disease and the subsequent need for healthcare services.

Registered Nurse Supply and Demand in 2035

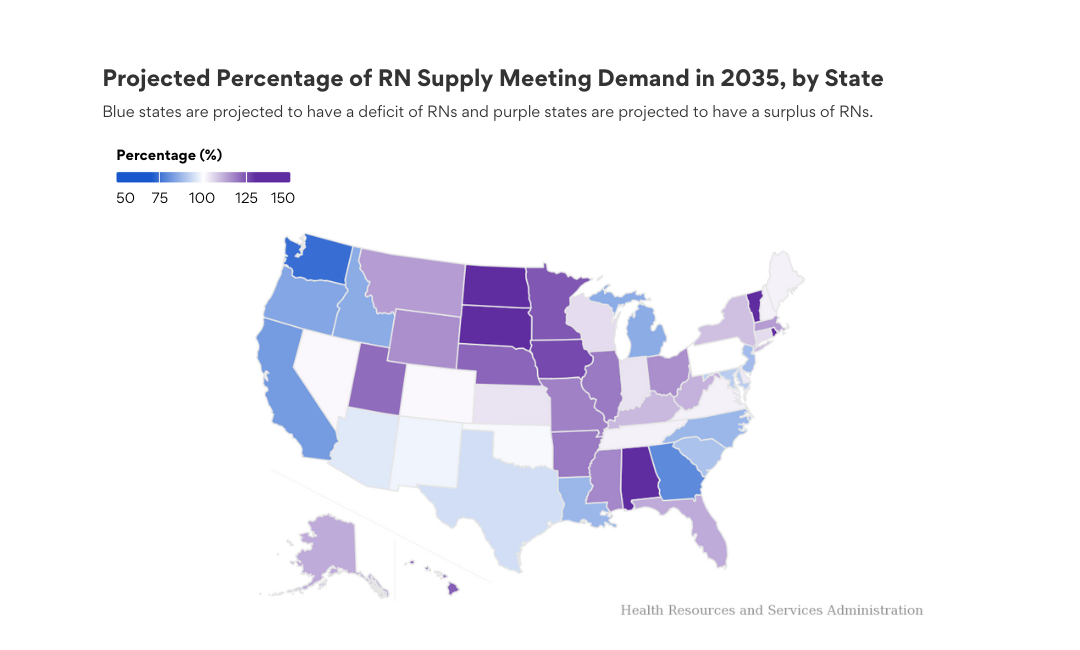

Currently, the nursing shortages are spread unevenly in regions across the U.S. and within different specialty areas. HRSA projections estimate that 15 states will continue to experience a shortage of full-time RNs in 2035, including Washington, Georgia, California, Oregon, and Michigan. RN shortages in nonmetropolitan areas are also projected to be significantly worse. HRSA data projects a deficit of over 12,000 RNs in nonmetropolitan areas in 2035.

The combination of the economic downturn, a rising number of retiring nurses, and an increase in healthcare demand has led to unsafe nurse-to-patient ratios, rising rates of burnout, and a subsequent departure from the profession.

Other factors that have contributed to the ongoing shortage include a shortage of nursing faculty, restricting a nursing program's ability to enroll and graduate an adequate number of nursing students.

As more individuals reach retirement age, the need for geriatric healthcare and the chronic diseases and comorbidities associated with senior adults increases.

Violence in the workplace has also played a role in the rising nursing shortage. The threat of physical or emotional abuse adds to an already stressful environment and lowers job satisfaction. Healthcare workers have a high risk of violence, with up to 38% having experienced some form of violence in their careers.

States With the Lowest Percentage of RN Demand Met in 2035

- Washington (74%)

- Georgia (79%)

- California (82%)

- Oregon (84%)

- Michigan (85%)

States With the Highest Percentage of RN Demand Met in 2035

- North Dakota (148%)

- Rhode Island (145%)

- South Dakota (142%)

- Vermont (140%)

- Alabama (134%)

When Could the Nursing Shortage End in Each State?

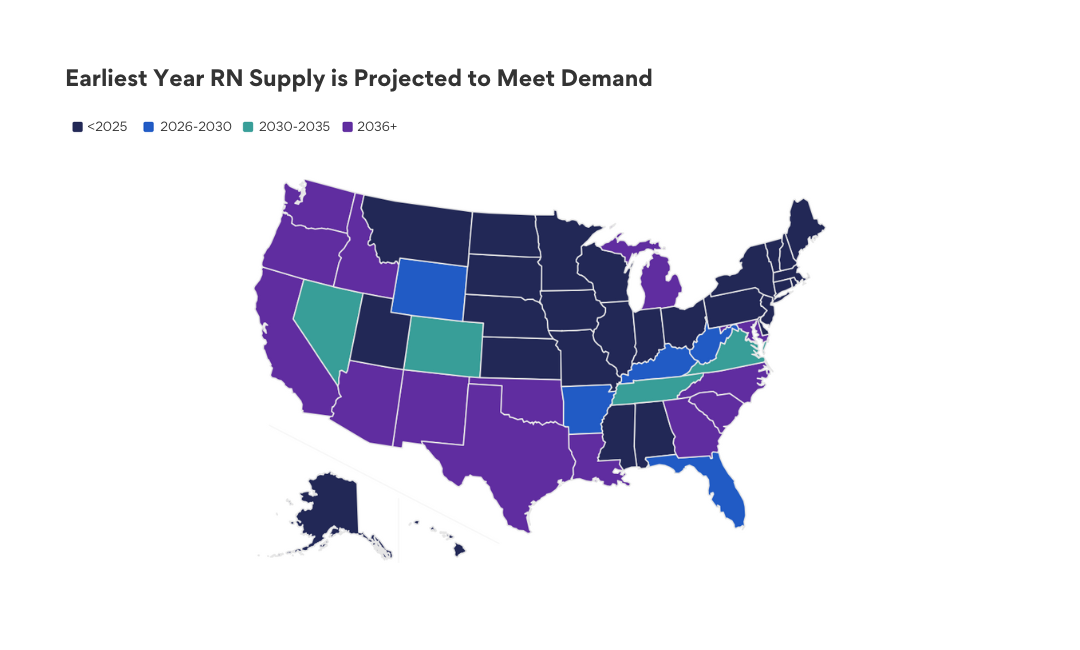

Using data from HRSA's nursing workforce projections, data shows the earliest year a state's supply of nurses could meet the healthcare demand. According to HRSA, much of the Northern U.S., from Montana east to Maine and New York, have already met statewide demand as of the initial data collection in 2020.

States in the West Coast and Southern U.S., except Mississippi and Alabama, are not expected to reach 100% adequacy until 2036 or beyond. Montana, Kentucky, West Virginia, and Florida are anticipated to reach demand between 2028 and 2030.

However, it's important to note that historical and future projections estimate that even after a state meets 100% of its demand, it does not mean that the nursing supply will be maintained. Factors contributing to these projections include the number of new nurses graduating within the state or attracted to work there.

Factors that impede a state's ability to reach adequate staffing include an aging workforce and a rising number of older adults who require a higher level of healthcare and a larger supply of nurses.

Closing the Gap

The determination that nursing supply meets demand must be predicated on a mathematical simulation that accounts for nurse-to-patient ratios. Nursing leaders and programs throughout the country are exploring options to help address their region's nursing shortage.

Federal and state money has been allocated to help develop nursing education programs that hope to graduate more students in the coming years. For example, William Paterson University recently opened the doors to a new school of nursing, and The Ohio State University has developed innovative programs to engage and teach nursing practice.

The Ohio Nurses Association (ONA) collaborated with Ohio lawmakers to propose the Nurse Workforce and Safe Patient Care Act that would standardize nurse-to-patient ratios and incentivize nursing graduates to work in Ohio. Interestingly, a 2023 survey by the ONA revealed that 42.8% of RNs who left the profession would consider returning if there were legally enforceable minimum staffing standards.

These are among the strategies nursing leaders and schools are considering and implementing to improve retention and attract more nurses. Adopting a diversified approach may shorten the time needed to end the nursing shortage.

This story was produced by NurseJournal and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.