Rural people don't practice religion more than their urban counterparts, survey shows

Rural people don't practice religion more than their urban counterparts, survey shows

The notion of a hyper-religious rural America, one that stands in direct contrast to a modern and secularizing urban America, is pervasive. But the numbers just don't support that stereotype.

Factors like income, race, partisanship, age, and education influence religious attendance more than geography does.

During my first semester of graduate school, I wrote a paper criticizing how National Geographic portrayed rural Appalachia. Without fail, National Geographic photographers always drew attention to the religious life of Appalachian communities — rural preachers, river baptisms, and little country churches.

But that image isn't entirely accurate. Only 54% of rural Americans identify as Christian, according to the Cooperative Election Study (CES), a 50,000-respondent national annual survey. That's about the same share of the metropolitan population that identifies as such. About 51% of respondents who live in metro counties said they were Christian, while 36% of both rural and metro people said they were atheist, agnostic, or nothing in particular.

Christianity is the dominant religion in both rural and urban areas, but about 2% of the rural population and 5% of the urban population identify as Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim, or Jewish.

Profession of a faith tradition does not directly equate to religious service attendance

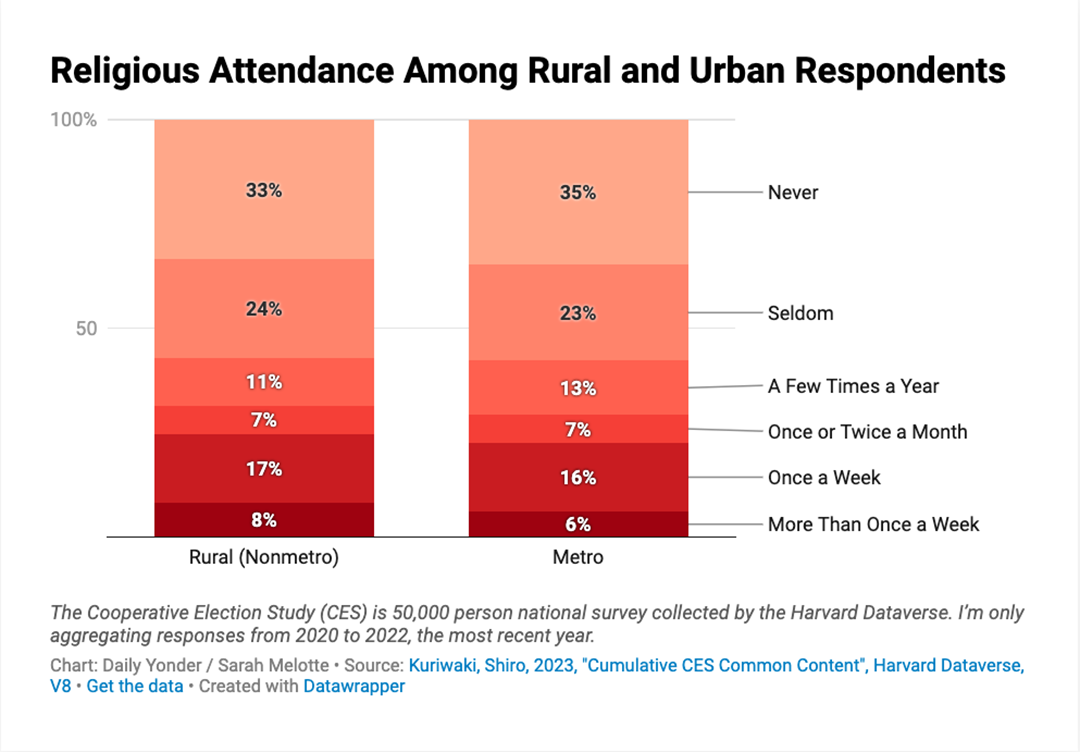

Fifty-seven percent of rural respondents said they either never or seldom attend church or another type of religious service, while only a quarter attend at least once a week. Attendance among metropolitan respondents isn't much different.

To calculate these numbers, The Daily Yonder used a variable the survey uses to measure attendance. The CES asked respondents to answer the question, "Aside from weddings and funerals, how often do you attend religious services?" This question captures individuals who attend a wide variety of religious services, not just Christian churches.

Despite stereotypes, geography doesn't do a good job of telling us who participates in organized worship each week. Religious attendance instead falls along other demographic lines. Differences between metropolitan and nonmetropolitan respondents do exist, as you'll see in the following graphics, but those differences pale in comparison to the gaps between demographic groups.

Let's go one by one.

1. Partisanship

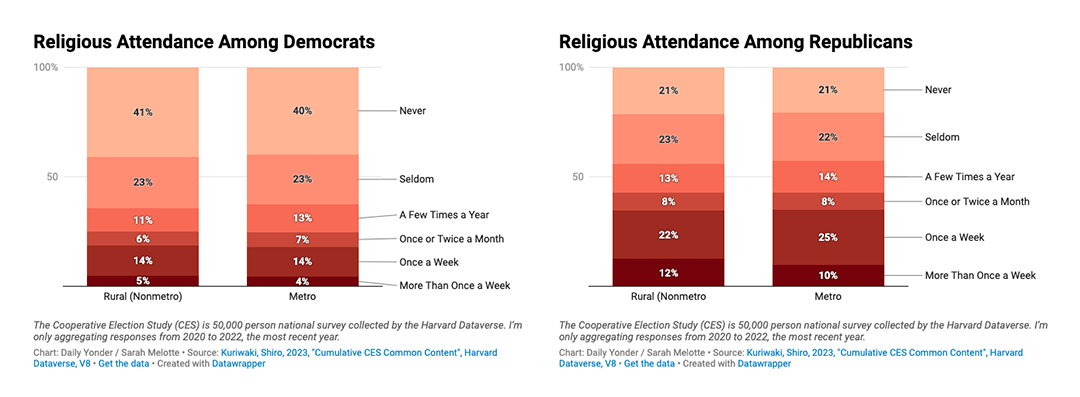

The biggest differences in attendance are between Democrats and Republicans, not rural and urban. Eighteen percent of metro and 17% of rural Democrats said they attend religious services at least once a week, almost 20% lower than the Republicans who attend that often. It's probably not surprising that Republicans attend church more often than Democrats, since more Republicans identify as Christian.

Forty-one percent of rural Democrats and 40% of urban Democrats say they never go, while never-attenders among Republicans only comprise about 21% of both rural and urban respondents.

Whether urban or rural, Republicans are more likely to attend religious services weekly (and less likely to never attend) compared to the population at large. And the opposite is true for the Democrats.

2. Economics

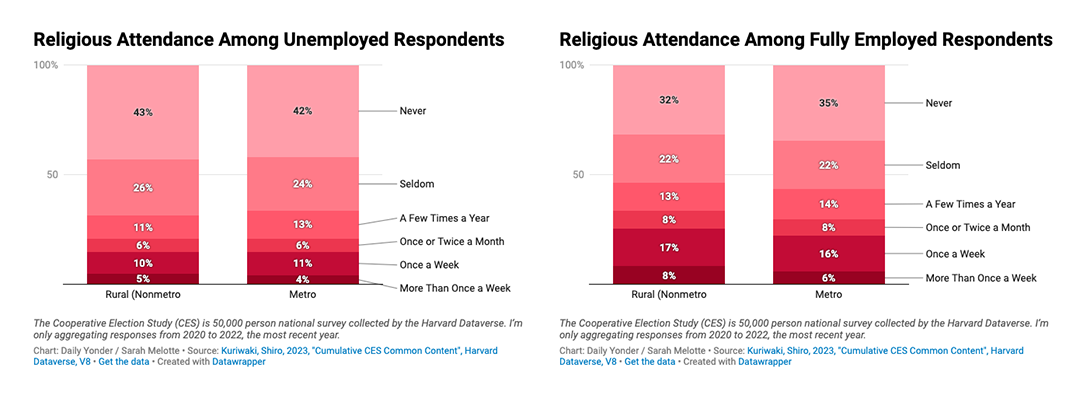

Unemployed and lower income people go to religious services less often. Only about 15% of both rural and urban unemployed respondents said they go at least once a week, compared to the quarter of total rural and urban respondents who said they go that often.

Forty-three percent of rural respondents and 42% of urban respondents who are unemployed said they never attend. That's almost 10 percentage points higher than the survey sample at large.

Religious attendance increases by another 10 percentage points among respondents who work full-time, with rural respondents slightly more likely to attend weekly compared to their urban peers.

A quarter of the rural respondents and 22% of urban respondents who work full-time said they go to a service at least once a week. In rural counties, attendance rates among fully employed respondents are 10 percentage points higher than unemployed respondents. In urban areas, that gap is 7 percentage points.

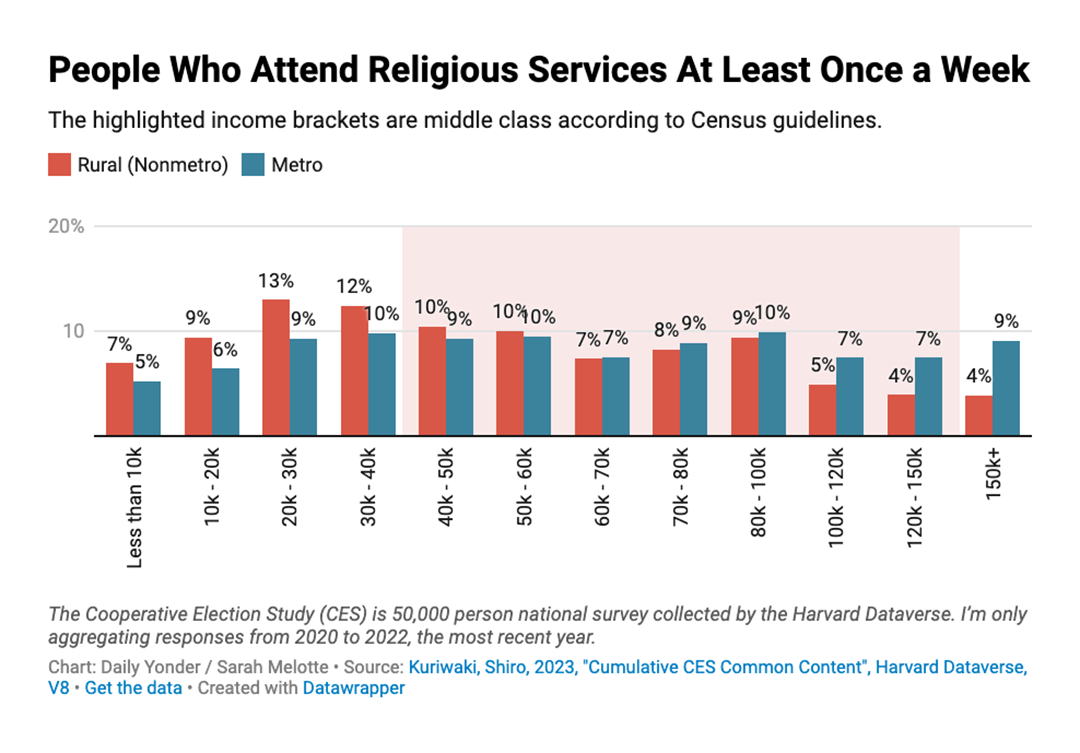

Income doesn't affect religious attendance as much as employment status, but there are slight differences among income brackets, as made clear in the following graph of the percentage of respondents who said they attend at least once weekly.

Lower income rural people attend services more often than urban people. But higher income urban people attend more often than rural people.

Rural respondents who make between $20,000 and $40,000 in annual household income are the most likely to attend at least once a week.

Attendance drops, although slightly, as income increases. Rural people who make more than $150,000 a year are one of the least likely groups to attend religious services at least weekly. Only 4% of rural respondents who make more than $150,000 said they go weekly, while 9% of urban respondents who make that much attend weekly.

What's interesting is that rural respondents who bring in less income attend religious services more often than urban respondents. But once we cross the threshold into households that bring in more than $60,000, attendance rates among urban respondents begin to increase over the rural respondents.

3. Race

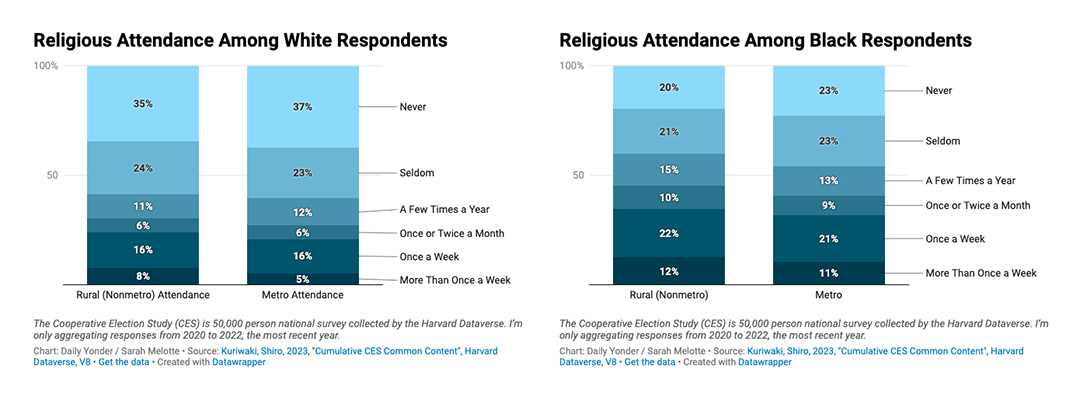

White respondents go to religious services less often than people of color. Only 24% of white rural respondents and 21% of white urban respondents attend at least once a week, while almost 30% rural people of color and 26% urban people of color go that often.

Weekly attendance among rural Black respondents was 10 percentage points higher than their rural white counterparts and 10 percentage points higher than the total rural attendance rate.

Thirty-four percent of rural Black people and 32% of urban Black people go to religious services at least once a week. Only 20% of rural Black respondents said they never attend, thirteen percentage points lower than white respondents.

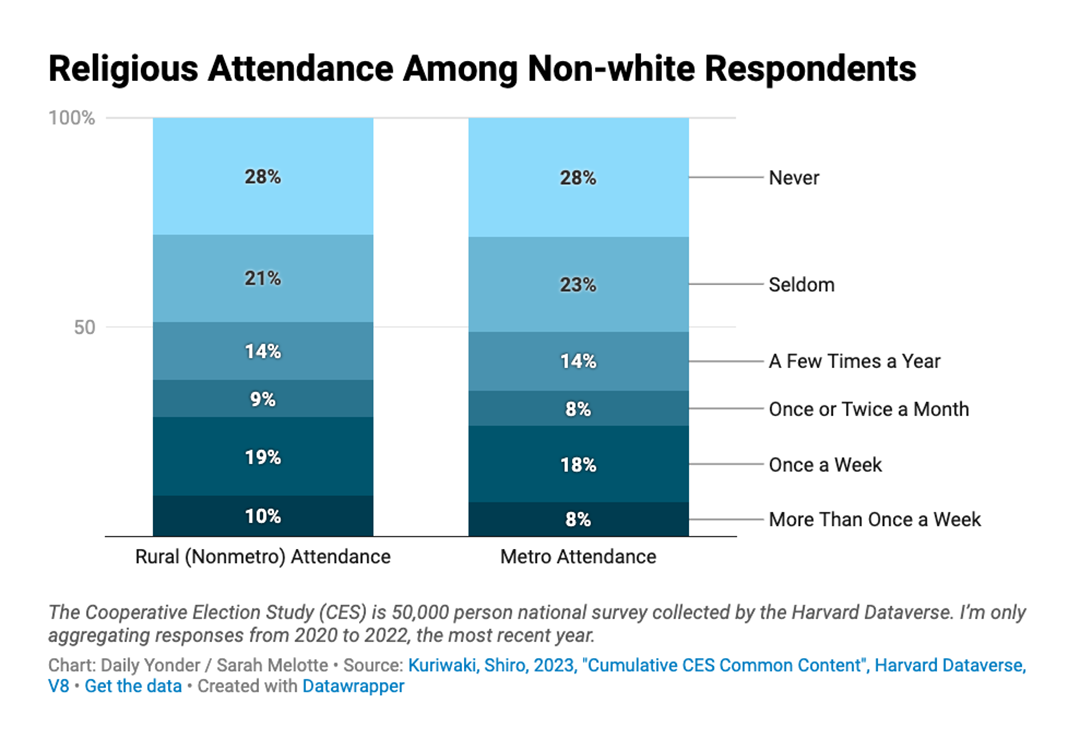

The percentage of non-white people who never attend is higher than the rate of Black never-attenders, but not as high as the white never-attenders

Because population numbers get really small when we break down the data by geography and racial identities other than Black and white (Hispanic, for example), I used all non-white respondents to look at church attendance among people of color. The data's limitations, unfortunately, don't allow us to explore the differences among different racial and ethnic groups who live in rural America with any precision.

In rural and urban areas, 28% of non-white respondents never attend, compared to the 35% of rural white and 37% of urban white people who never attend.

4. Age

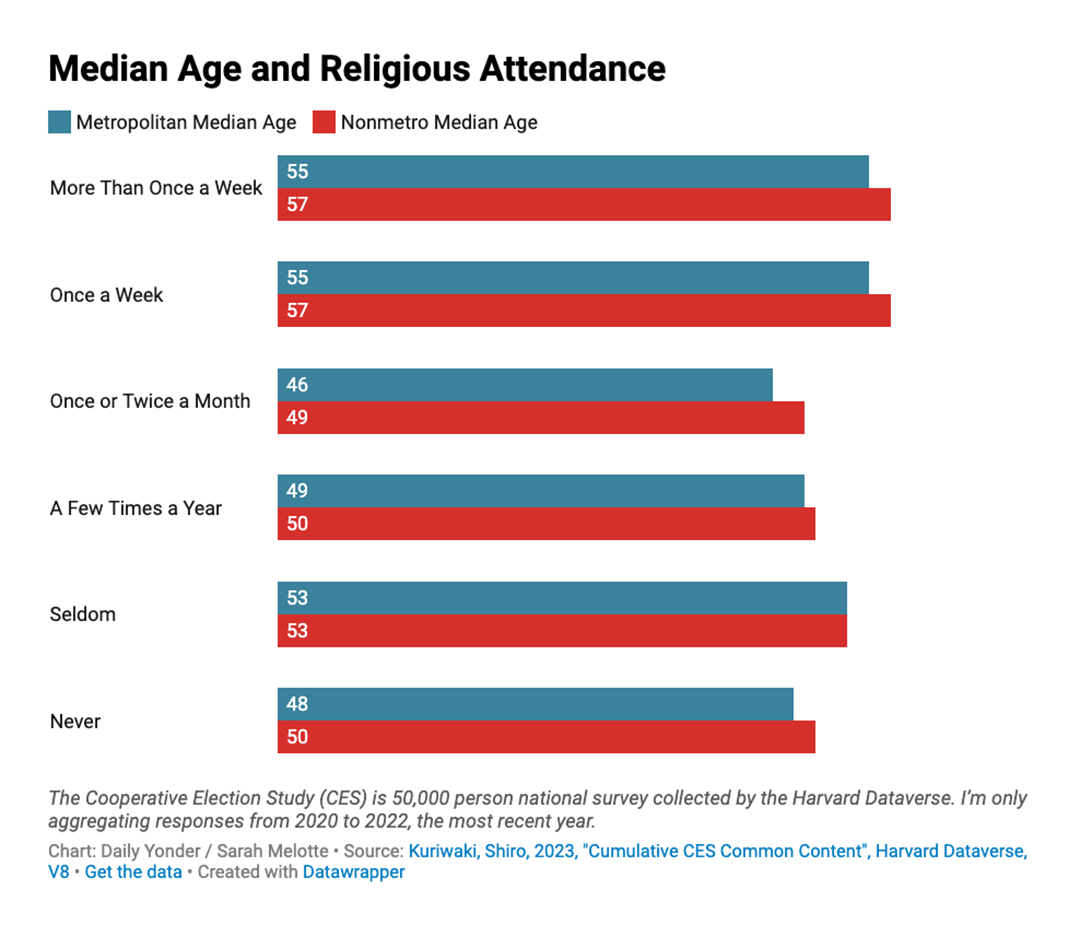

People who attend religious services at least once a week are slightly older than other respondents, especially in rural areas. The median age of people who attend at least once a week is 57 years old in rural areas, and 55 years old in urban areas.

People who attend once or twice a month, on the other hand, are younger than the other groups. In rural areas, the median age of people who attend once or twice a month is 49 years old. In urban areas, the median age is 46 years old.

5. Education

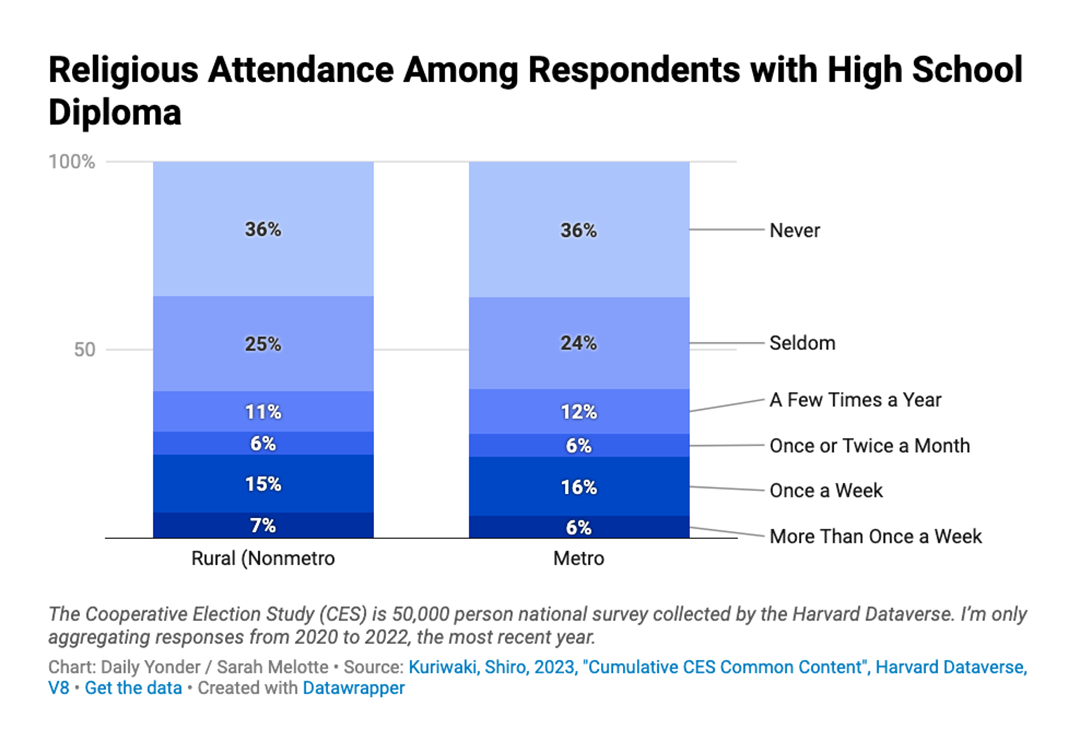

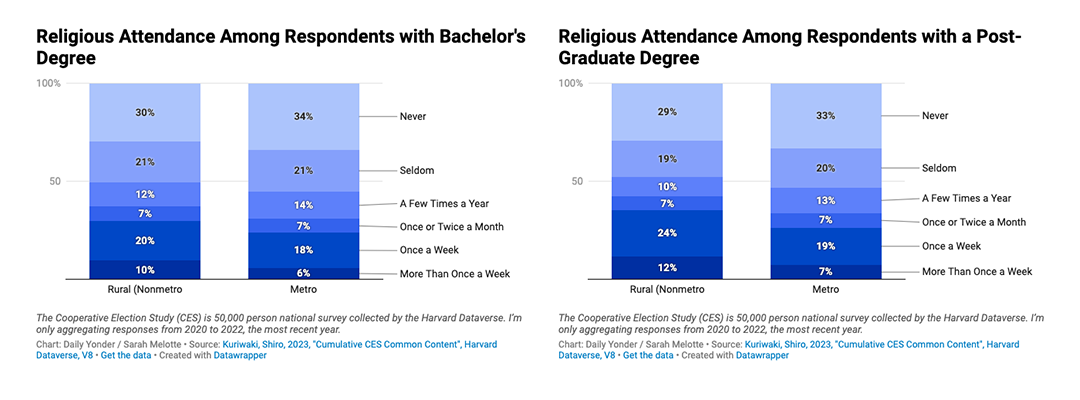

In the previous examples, we saw that the gap between urban and rural attendance was insignificant compared to the gap between other demographic groups. But when it comes to education, we see a bigger divergence between rural and urban people and their rates of attendance.

For rural respondents, the higher the level of education, the more they attend religious services. But educational attainment among urban respondents doesn't have as big of an impact on attendance as it does on rural ones.

Thirty percent of rural respondents with a bachelor's degree attend church at least once a week, 8 percentage points higher than rural people with only a high school degree.

About a quarter of urban and rural respondents with high school degrees said they attend at least once a week. That number stays relatively stable among urban residents who have bachelor's and graduate degrees. But attendance increases with educational attainment for rural residents.

Having a graduate degree increases religious attendance among rural respondents by 6 more percentage points above those who have a bachelor's degree

Editor's note: The Daily Yonder's rural definition is based on the metropolitan classification system from the Office of Budget and Management (OMB). All counties not defined as metropolitan by the OMB were used as a stand-in for rural.

This story was produced by The Daily Yonder and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.