How do the National Archives work? 6 things you need to know now that Trump's case has put them in the spotlight

How do the National Archives work? 6 things you need to know now that Trump's case has put them in the spotlight

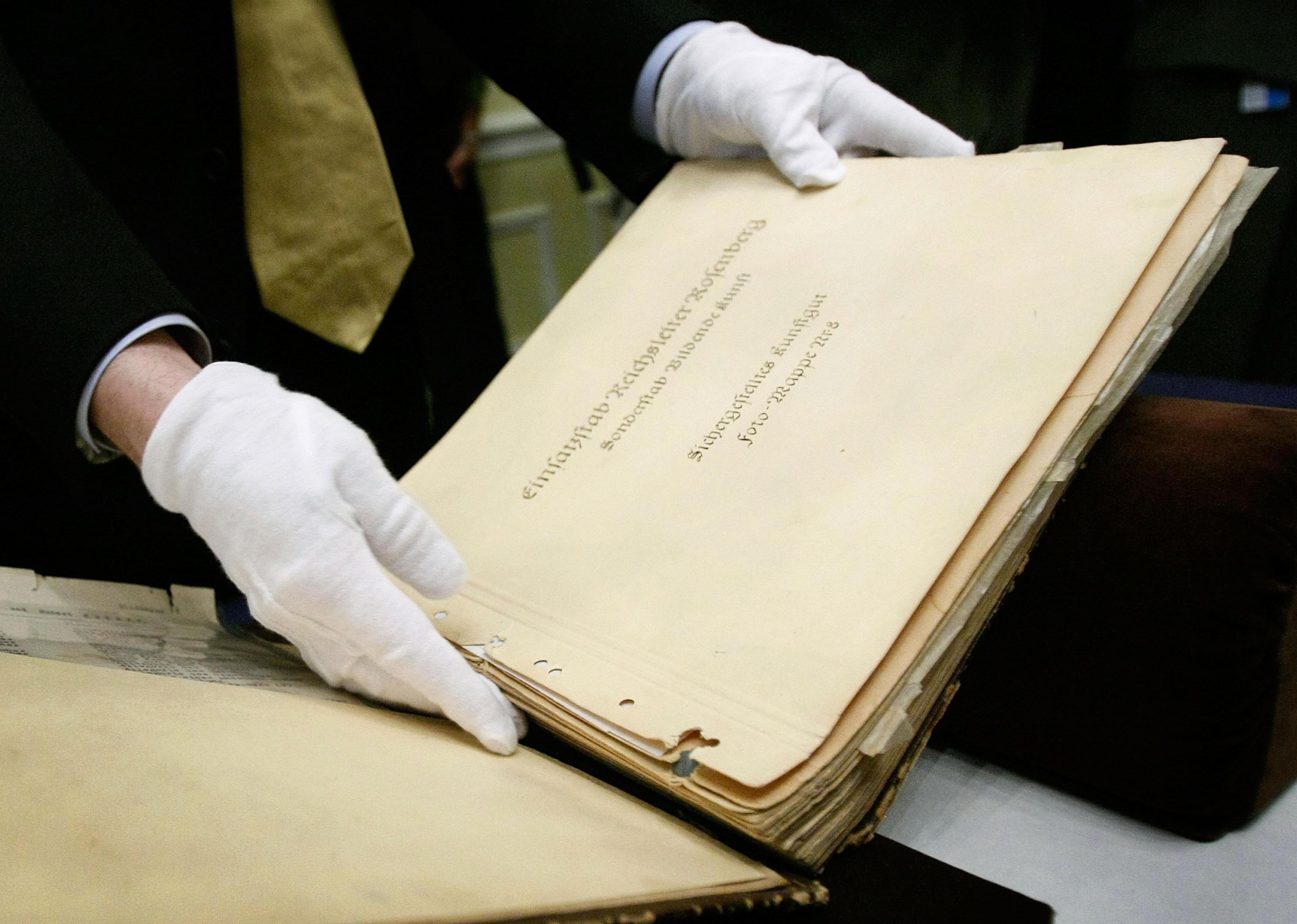

Federal agents' Aug. 8 raid on former President Donald Trump's Mar-a-Lago residence thrust executive recordkeeping into the national limelight. Since then, one institution—the National Archives and Records Administration—has been on the tip of many news journalists' tongues. However, it is one unfamiliar to many Americans.

Before the August raid, NARA retrieved 15 boxes of White House records from Trump's Florida residence this past February—documents containing information from the FBI, the National Security Agency, and the CIA, all of which should have been in NARA's possession from the start.

The investigation into possible wrongdoing on the part of the former president is ongoing. Officials are still searching for more documents under the auspices of the Presidential Records Act of 1978. Archivist for the U.S. David Ferriero told NPR the Act "mandates that all Presidential records must be properly preserved by each Administration so that a complete set of Presidential records is transferred to the National Archives at the end of the Administration."

Stacker compiled a list of things you may not know about the National Archives. Among myriad other records, the Archives holds the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, Lee Harvey Oswald's Selective Service Card, and the letter Elvis Presley sent to President Richard Nixon.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the National Archives in 1934 as "the nation's record keeper," a repository for the care and preservation of U.S. government documents. The Archives presently holds more than 13 billion pages of textual records; 10 million maps, charts, and architectural and engineering drawings; 44 million still photographs, digital images, filmstrips, and graphics; and nearly 1 million video and sound recordings, along with thousands of other holdings.

When and why were the National Archives created?

Before the creation of the National Archives, the United States did not have a designated place to store government documents. Instead, the U.S. scattered federal records in several basements, attics, and even abandoned buildings, all lacking security.

Congress passed the Public Buildings Act In 1926, which would eventually provide an avenue for creating a National Archives building. Architect John Russell Pope drew up plans for such a building in 1931, and ground broke on its construction soon after. Even though work on an archive building had already begun, it wasn't until 1934 that President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed legislation to create the National Archives.

The building's construction finished in 1937, and historian and archivist Robert D.W. Connor became the first official archivist of the United States, leading a team of 80 staff members.

What types of documents does it collect and store?

According to the National Archives website, the Archives holds "historical U.S. government documents (federal, congressional, and presidential records) that are created or received by the President and his staff, by Congress, by employees of Federal government agencies, and by the Federal courts in the course of their official duties." In other words, its catalog is a kind of living record.

What types of documents the Archives maintains are various and wide-ranging. The Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, and the Bill of Rights are likely the most well-known historical documents under NARA's responsibility. The Archives also contains the original note cards from Ronald Reagan's 1987 speech in Berlin—where he famously demanded, "Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!"

Other documents in the Archives include the Zimmerman Telegram, which helped goad the U.S. into entering World War I in 1917, and the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, which declared that all enslaved persons "are, and henceforth shall be, free."

How are items determined to be archive-worthy?

The operational mission of the National Archives is the idea that government records belong to the people because the United States is a democracy. The Archives are meant to "help us claim our rights and entitlements, hold our elected officials accountable for their actions, and document our history as a nation."

However, only 2-5% are earmarked for the permanent collection, as the Archives only include federal records determined to have continuing value. NARA does not catalog most of the paperwork and other tangible or digital communications between government employees in a given administration.

Examples of such records of continuing value, both for posterity and for research and access by the people, include Japan's documents of surrender to the Allied Forces in WWII, firsthand accounts of the earliest explorations of antarctic and sub-arctic regions, and photo documentation of various periods in American history, from the Dust Bowl to the civil rights movement to 9/11.

During the federal government's seizure of records from Mar-a-Lago, the Archives sought several qualifying documents from the Trump administration, including original letters to the president from North Korea's Kim Jong-un and President Barack Obama's handwritten note for Trump upon leaving office.

How do the National Archives get the material?

Documents created by or for the government automatically get transferred to the National Archives. Presidential materials are published initially in the daily Federal Register. At the end of a presidential administration, before the newly elected president officially assumes command of the nation, all files and documentation of the previous administration not essential to the incoming leadership are collected and transferred to NARA for curation.

Private citizens possessing historically significant records may donate the items to the Archives for care and inclusion.

All government documents are considered public domain and thus available for public use and research. Original documents are not lent out for research purposes—you have to request of copy of them; however, the Archives has often lent documents to exhibits.

Have documents ever been stolen from the Archives?

Yes, they have—several times.

In 1987, Brooklyn, New York-born artist and art historian Charles Merrill Mount stole 400 documents from the Archives, among them a trio of letters by Abraham Lincoln, which he attempted to sell to a Boston bookstore owner. The attempted sale sealed his fate, as FBI agents were waiting to arrest him at the designated time of the exchange. His sentence was five years in prison.

Not 20 years later, in 2002, having not learned from Mount's failed example, a court convicted curator Shawn Aubitz of boosting hundreds of documents and photographs, including presidential pardons, in 2000. He placed select items on eBay, which drew the attention of a National Parks Service employee, who blew the whistle on him. He wound up doing 21 months in federal prison and owing $73,000 in restitution.

Like a trio of fallen dominoes, three thefts occurred in 2003, 2005, and 2006. The first involved Sandy Berger, former national security adviser for the Clinton administration, who would slip classified documents into his suit jacket and store them in a remote location for later retrieval. That cost him a $50,000 fine and 100 hours of community service; he also lost his security clearance and law license.

Two years later, the courts sentenced Howard Harner to two years for stealing more than 100 Civil War-era documents and putting them on eBay. And the following year, unpaid NARA intern Denning McTague bested Harner's score by taking 164 Civil War-era records—also putting them up for sale on eBay.

In 2011, the National Archives banned author and physician Thomas Lowry after he altered the date of a pardon issued to a Civil War soldier by Abraham Lincoln. That same year, Barry Landau and Jason Savedoff stole 10,000 documents from the Archives, among them reading copies of speeches delivered by Franklin D. Roosevelt and possessing his handwritten notations. Savedoff was sent away for 12 months and a day, while Landau received seven years.

The latest known National Archives theft happened in 2018. Antonin DeHays, a historian and professor, stole many World War II-era items, including soldiers' dog tags and even pieces of downed U.S. aircraft. He was sentenced to 364 days in prison, three years of supervised release, and received a $43,000 fine.

How can you view the Archives?

The National Archives are open to the public for in-person visits. The main building and museum are in Washington D.C. However, there are many others around the U.S., including various federal records centers, extensions of the National Archives in cities like Chicago, Boston, and Atlanta, and presidential libraries and museums devoted to the records and history of specific presidents.

Research rooms require appointments and advanced virtual consultations, especially for buildings outside of Washington D.C.

The Obama administration made presidential records digitally accessible to the public. Many items in the Archives are available online, and NARA's Electronic Records Archives are only getting more expansive.