This story was produced by Guava Health and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.

Why do so many women get POTS?

POTS, or Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, isn't new to the medical world, but it has sparked special interest in the women's health sphere in the past few years. So what's with all the fuss?

As reported by Guava Health, there are a few reasons why POTS is gaining so much attention. For one, the COVID-19 pandemic seems to have led to a significant uptick in POTS diagnoses, especially among women. In the past few years, we've also had a lot more access to medical information, whether that be through academic journals, forums, or online communities. In turn, POTS advocates, armed with the knowledge of their peers and medical communities, have spearheaded awareness efforts with the hope of learning more about the treatment, management, and diagnosis of this unique disease.

All this talk about POTS raises new questions about who's affected and why. As of 2019, almost 95% of POTS patients were women, which, as far as chronic disease demographics go, is a pretty striking number.

Despite this staggering difference in women and men being affected by POTS, very little research has gone on that actually begs the question: Why?

What is POTS?

To get oriented, let's first provide a framework for what POTS is. It stands for Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, but the acronym alone doesn't quite clear it up.

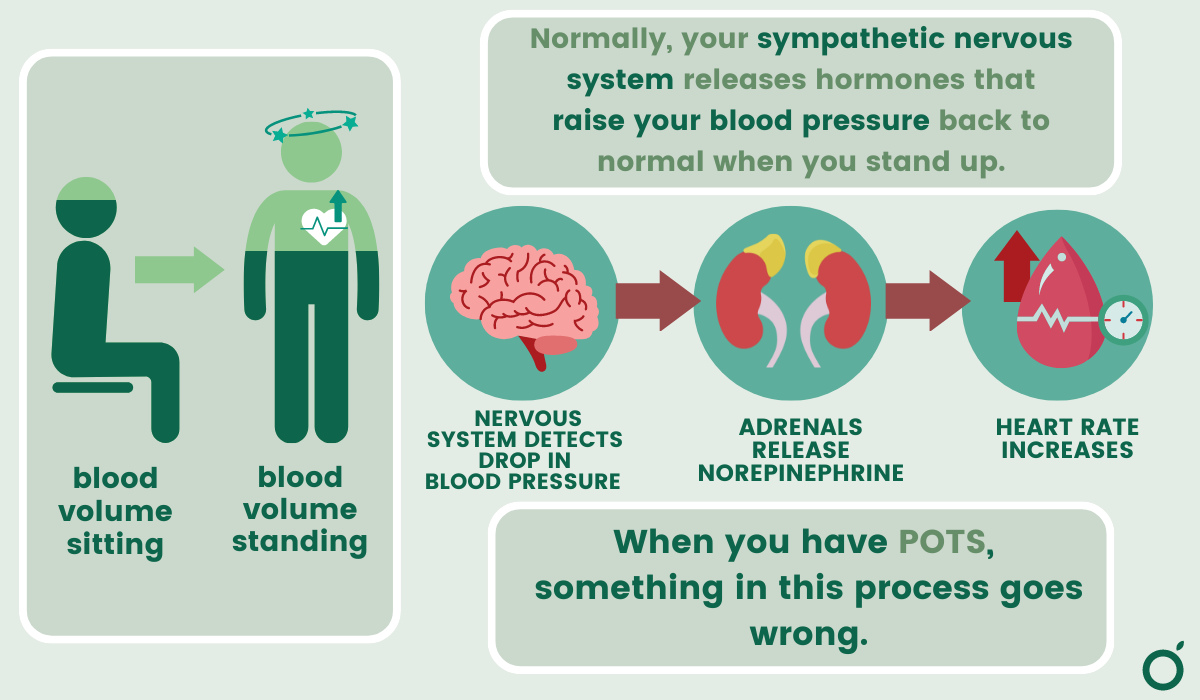

POTS is a disorder that affects the autonomic nervous system, which controls bodily functions you don't consciously control, like breathing, heart rate, digestion, etc.

Its main symptom is an abnormal spike in heart rate without low blood pressure when you move from lying down to a standing position. The spike tends to be accompanied by symptoms like dizziness, lightheadedness, and fatigue, which can take a massive toll on the quality of life for some patients.

What does the current research say?

POTS seems to be caused by countless factors. For some people, it's problems with the nervous system, for others, it's abnormalities in connective tissue, while some people simply have low blood volume. But why is it that women are so prone to POTS?

Hormonal influences

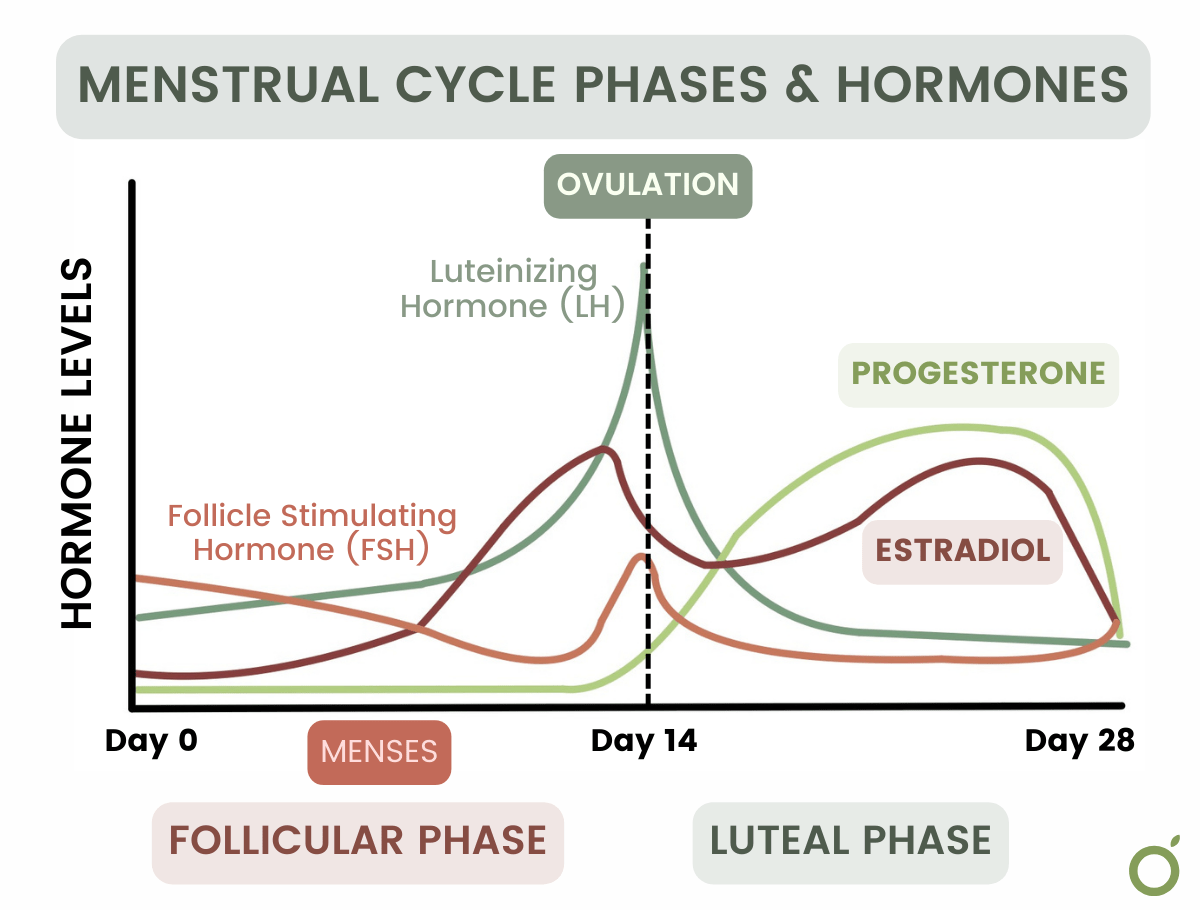

There are a few studies suggesting that hormonal changes, especially those related to the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and puberty, might influence the onset and severity of POTS symptoms. Given the age range of affected women (15-50 years old) and the average age during menstruation, these explanations make a compelling argument.

This study from 2010 found that certain markers for POTS were more timid during the mid-luteal phase (between ovulation and menstruation) than in the early follicular phase (menstruation). They attributed this to the mid-luteal phase having higher progesterone and estrogen levels, thus offering a sort of "protection" from POTS by activating critical regulators of things like blood volume and electrolyte balance. This was a particularly small sample though (it compared 10 women with POTS to 11 without), so there's certainly room for more research.

What this research and other studies suggest is that POTS often has something to do with the sympathetic nervous system, which might be influenced by female menstrual cycles. The sympathetic nervous system is a branch of the autonomic nervous system, but it specifically regulates your "flight or fight" response, which does things like increase heart rate when you stand up or do exercise.

Differences in nervous system activity

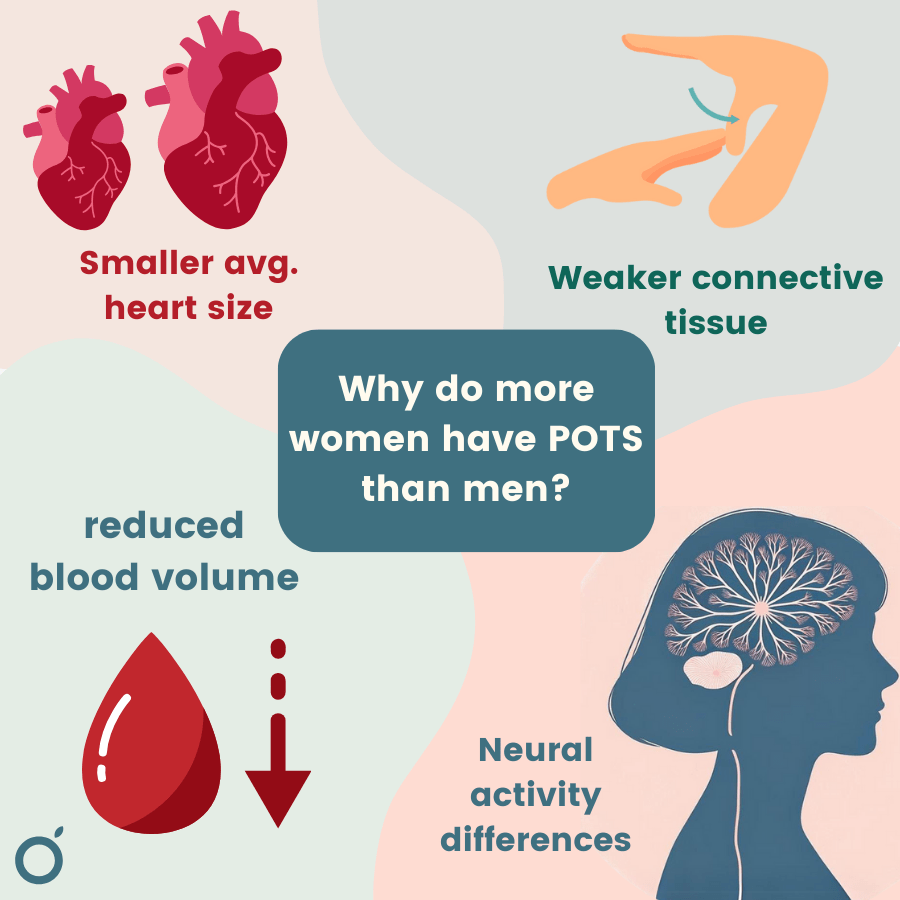

But this isn't to say that women's cycles are causing POTS, nor does it explain why women experience POTS symptoms more than men. A study from last year attributes more women having POTS to weaker sympathetic nervous activity. According to their findings, women's nervous systems don't adjust as efficiently to getting up too quickly, thus causing more issues with heart rate and lightheadedness.

A prominent 2005 study, however, begs to differ. Researchers found that there was not nearly enough of a difference in sympathetic reactivity to account for the discrepancy between men and women. Instead, they think it has more to do with differences in structure and physiology.

Anatomical differences:

So, what else might we consider if differences in hormones or nervous systems don't quite explain everything? Some experts think we need to look closer at the nuances in female anatomy to answer our question.

Dr. Julian Stewart, a pediatric cardiologist at New York Medical College, brought up that "women may be disproportionately affected in part because of their reduced blood volume compared to men (even correcting for size)." With less blood to work with, women's hearts and nervous systems might end up working harder to push enough blood back up to the brain and upper half of the body. Women also seem to have smaller, stiffer hearts than men, impacting how well they can push blood out to the rest of the body when needed.

In addition to differences in heart size and blood volume, women are more likely to have issues with over-flexible connective tissue. In severe cases, this is called joint hypermobility syndrome or Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS). This article by Guava looks at why POTS and EDS tend to go hand-in-hand, but the main point is this: EDS patients have stretchier tissue around their blood vessels, which makes it harder to constrict to push fluid upward. So, the body has to pump out more stress hormones to accomplish the same blood movement as someone without EDS.

Autoimmune factors

For reasons that aren't well understood, quite a few POTS patients (about a sixth) also suffer from an autoimmune disease. Coincidentally, as of 2004, 80% of people with autoimmune disorders were women.

Autoimmune disorders occur when your immune system starts unnecessarily attacking your own body, which as you'd expect, causes several issues. It does this by making "autoantibodies,"' or "self antibodies," that target your own cells instead of only foreign ones.

Studies have found that some POTS patients have autoantibodies that target certain neuronal "hardware" involved in the autonomic nervous system. By interfering with this pathway involved in heart rate regulation, blood vessel constriction, etc., these autoantibodies may be to blame for POTS in several individuals.

Conclusions

So, why do so many women get POTS? It turns out, it's pretty complicated. The reasons range from hormonal differences affecting nervous system function to physical differences like smaller hearts and more elastic connective tissue in women. Plus, there's a strong link between POTS and autoimmune diseases, which tend to hit women harder.

Now that the spotlight on this condition has intensified post-COVID-19, it brings up a broader issue in medical research: the need for insights into chronic illnesses that are specific to women's health. Although the past 30 years have seen a significant uptick in research specific to women, there's still plenty of work to be done to improve the lives of women with chronic illnesses.

This article uses 'women'/'men' and 'male'/'female' to describe people assigned female/male at birth to reflect the language of the studies cited. We acknowledge that gender identity and gender assigned at birth do not always align.