New caffeinated drinks are hitting restaurants. Do you know how much caffeine is too much?

This story originally appeared on Top Nutrition Coaching and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

New caffeinated drinks are hitting restaurants. Do you know how much caffeine is too much?

Caffeine is the world's most used drug, with an overwhelming majority (88%) of Americans saying they consume caffeine. Of those who do, about 4 out of 5 say they consume caffeine on a daily basis, while nearly half consume it multiple times throughout the day, according to March survey data released by the International Food Information Council.

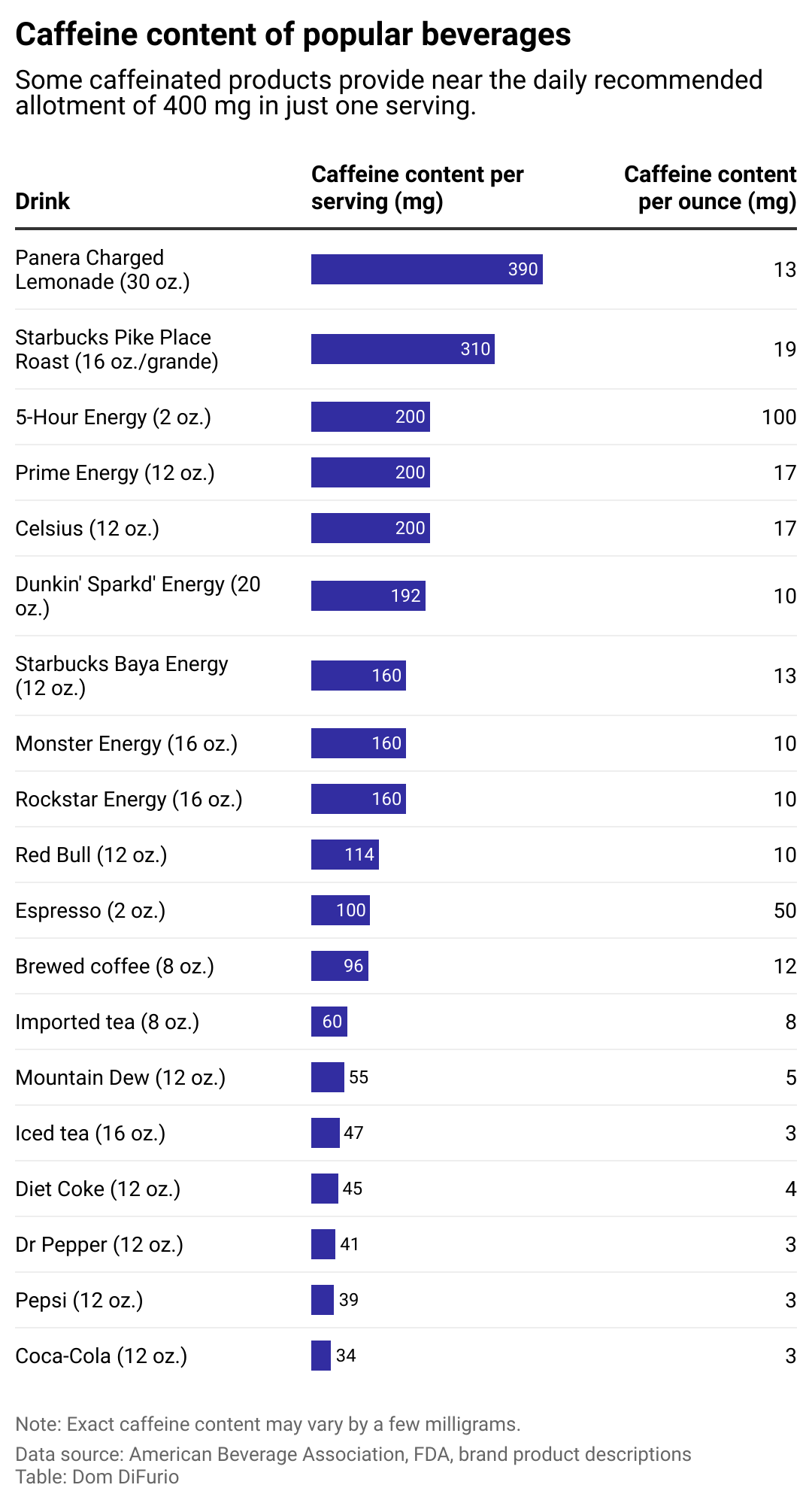

Yet only 6% of those surveyed were aware that the Food and Drug Administration recommends 400 milligrams as the safe allotment of caffeine to ingest in a single day. That's the equivalent of about four 8-ounce cups of coffee brewed at home—or just one Charged Lemonade from Panera Bread.

Panera's infamous and highly caffeinated Charged Lemonade drink first debuted in 2022 as part of the fast-casual bakery's subscription drink program with unlimited refills, allowing customers to drink as much as they chose. In May, Panera announced the drink would be phased out of restaurants after allegedly contributing to several deaths and generating multiple lawsuits.

However, the market forces that influenced its addition to the menu in the first place remain, and more fast food brands are announcing new, caffeinated drinks. Over the last decade, energy drinks have been one of the fastest-growing beverage categories for companies, signaling consumers can't get enough of them. In a sign these drinks may become more common at quick service restaurants, Dunkin' announced one of its own in February called Sparkd'.

Caffeine is among the most studied drugs. But how much do consumers know about the caffeine they're putting in their bodies?

Top Nutrition Coaching analyzed data from the International Food Information Council, the Department of Agriculture, the Mayo Clinic, and various beverage companies to illustrate the caffeine contents of popular drinks as new caffeinated beverages snag headlines for their risks.

Everyone's caffeine sensitivity varies, and certain populations, including pregnant people, should keep their caffeine intake even lower than the recommended 400 mg. Caffeine can make a person irritable and anxious, cause sleep problems, and result in a fast heartbeat. It has been linked to other health issues, and in rare cases, potential for death, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Caffeine is relatively safe to consume in controlled amounts. But the risks are heightened when consumed without knowledge of how much caffeine is entering the body, or when mixed with alcohol and other drugs. Sometimes, ambiguous advertising or disclosures make it difficult to discern just how much you're consuming—as some of the lawsuits leveled against Panera have alleged.

Newer beverages—and marketing tactics—push limits of daily intake

Energy drinks have received public scrutiny since hitting the mainstream beverage market in the 1990s. But the beverage industry has largely defended them by drawing comparisons to the caffeine content of a cup of coffee. There are no set limits on the amount of caffeine that can be put in retail foods and drinks in the U.S., unlike in Canada, where drinks can't contain any more than 180 mg. That law led Canadian regulators to pull popular energy drink Prime Energy from YouTube star Logan Paul off of shelves last year.

Many mainstream energy drinks that have been on U.S. shelves for decades—like Rockstar, Red Bull, and Monster—contain roughly 10 mg of caffeine per ounce. That's roughly on par with the typical cup of coffee. However, those brands of energy drinks also come in 16-ounce cans. That's twice the size of an 8-ounce cup of coffee—and nearly twice the caffeine.

For years, energy drink brands have built appeal and loyalty among American consumers, and men in particular. Monster Energy and Red Bull have both spent decades building exclusive-feeling brand identities heavily linked to extreme sports, pushing the idea that the beverages provide energy for adventurous lifestyles and doing extraordinary things. Studies have shown that energy drink use is often associated with other risky behaviors like illicit drug use as well as with poor diets.

Monster energy targets a young audience, particularly men, who want to enhance their focus and performance. The brand avoids traditional marketing channels and uses social media or influencer marketing to build loyalty, creating a certain mystique around the drink that has nothing to do with its caffeine content. It's not dissimilar from Red Bull's famously exclusive marketing approach, which focused on the energy boost among athletes after chugging one—not the drink itself.

When the large-sized Panera Charged Lemonade entered the market, "energy" had already become distinct from "drink." That posed a problem: Charged Lemonade contained almost the equivalent caffeine content as four to five Red Bulls, depending on whether you were to drink the standard small 8.4-ounce cans or slightly larger 12-ounce cans.

That high caffeine content has been the subject of at least three lawsuits filed against Panera in the last year alleging it contributed to the death of young customers.

To avoid adverse health effects from caffeine, consider slowing down your consumption of caffeinated drinks and taking measures to cut back. The Mayo Clinic recommends reviewing and making changes to your diet if you're regularly drinking the maximum amount of recommended caffeine per day, or about four cups of coffee. And, who knows—maybe you'll even sleep easier at night.

Story editing by Alizah Salario. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.